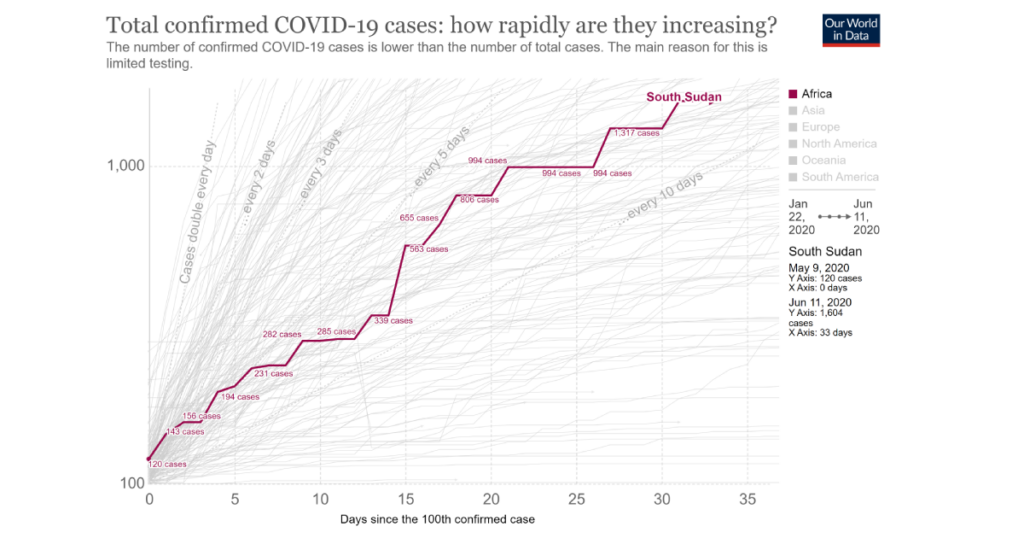

It is close to two months since South Sudan recorded its first Coronavirus case, making it among the last countries to report the presence of the virus in East Africa. Following the announcement, the number of confirmed cases increased rapidly.

South Sudan now has more than 1,600 confirmed Coronavirus cases and 24 recorded deaths.

What seems to be more worrying is that the virus is spreading quickly. In early May, the number of cases were doubling every 5 days. According to the latest data, cases are doubling every 16 days, making South Sudan one of the countries with a faster growth of the virus worldwide. This data also doesn’t account for cases that aren’t confirmed through testing.

Why does the virus spread so quickly?

Covid-19 is a new virus spreading rapidly around the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) says “people can catch COVID-19 from others who have the virus. The disease spreads primarily from person to person through small droplets from the nose or mouth, which are expelled when a person with COVID-19 coughs, sneezes, or speaks.”

Experts around the world have described COVID-19 spread as ‘exponential growth.’ This means each infected person can infect multiple new people. Without lockdown, isolation, or distancing measures, cases can continue to multiply rapidly, spread from person to person. Thus if the current trends continue in South Sudan, even though our current reported cases are only at 1,604, the country could quickly surpass neighboring countries like Sudan, which now stands at more than 6,000 confirmed cases.

What is South Sudan doing to try to stem the spread?

Covid-19 hit South Sudan at a time when more than 150 countries globally were already combating the spread of the deadly virus; a lot of countries were put to test on their level of disaster preparedness and health systems capabilities, including the United States, Italy, Sudan and South Africa.

Not so different from other countries, the South Sudanese government was swift to outline directives that saw all restaurants to remain open but should only offer takeaway services, adding that shops selling non-food items must remain closed until further notice.

The government also directed that all funeral gatherings must be limited to less than five people, to avoid spread of the virus at the events. The health ministry also directed citizens to wash their hands regularly and avoid large gatherings.

South Sudan also has reported that it is following a strong contact tracing approach. This involves finding people who were in contact with someone who has tested positive for the virus, and isolating those people in case they are also sick, so that they don’t spread it further.

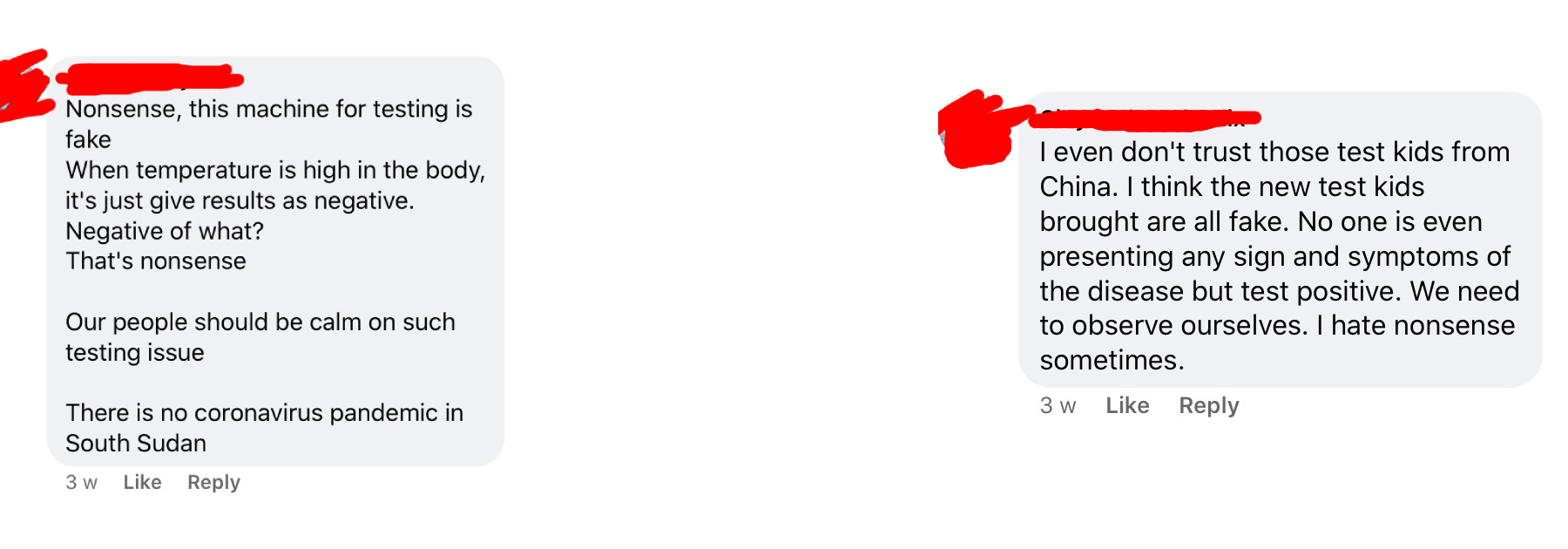

The level of lack of awareness on the virus is quite huge among South Sudanese; this is also evident in social media where different online users have continued to fabricate information on the spread of the virus.

Community-based organizations and different NGOs that operate within South Sudan also began sensitization campaigns which aimed at educating the citizens about the novel coronavirus.

Are the actions working?

Despite all the effort to stop the spread of Coronavirus, the reality on the ground is quite different. Several churches in South Sudan still held Sunday mass service despite warnings to restrict public gatherings to contain the virus.

There have been reports that traders in different markets are still acting the same way, not adhering to the government directive of keeping social distance and washing hands with soap and running water.

Certain local cultures and myths can also lead to ignorance about the dangers of the pandemic. One resident in Bor town, Simon Manyok, told Radio Tamazuj in April that “handshakes are part of our cultures. And if someone fails to do so, those in the villages will hold grudges against you.”

He and other community members expressed mixed reactions on the government’s decision to ban all public gatherings.

“People will only adapt to these new lifestyles if the government carries intensive campaigns in cattle camps and residential areas,” Manyok said.