More than 70 percent of the South Sudanese population will struggle to survive the peak of the lean season in South Sudan this year as the country grapples with unprecedented levels of food insecurity caused by conflict, climate shocks, Covid-19, and rising costs, warned the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) on Friday.

According to WFP, While global attention remains fixated on Ukraine, a hidden hunger emergency is engulfing South Sudan with about 8.3 million people in South Sudan – including refugees – will face extreme hunger in the coming months as the 2022 lean season peaks, food becomes scarce and provisions are depleted, according to the latest findings published in the 2022 Humanitarian Needs Overview.

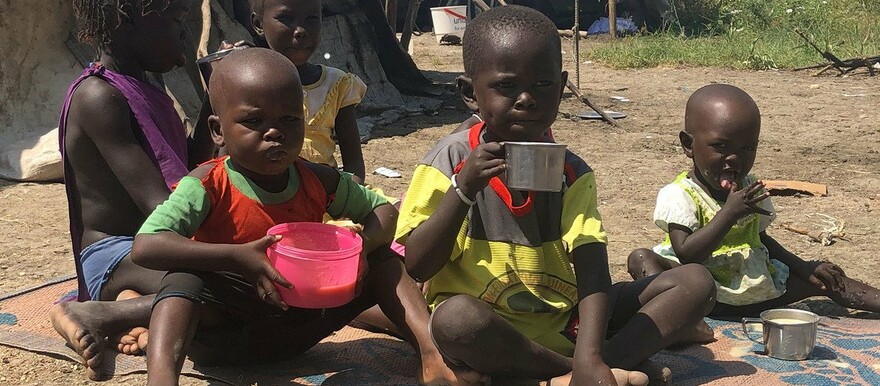

Particularly at risk are tens of thousands of South Sudanese who are already severely hungry following successive and continuous shocks and could starve without food assistance, a WFP press statement said.

Adeyinka Badejo, Deputy Country Director of the WFP in South Sudan painted a grim picture of the looming situation.

“The extent and depth of this crisis is unsettling. We are seeing people across the country have exhausted all their available options to make ends meet and now they are left with nothing,” Badejo said.

While providing critical food and nutrition assistance to meet the immediate needs of populations at risk, WFP simultaneously implements resilience-building activities to help these communities cope with sudden shocks without losing all their productive assets.

“Given the magnitude of this crisis, our resources only allow us to reach only some of those most in need with the bare minimum to survive, which is not nearly enough to allow communities to get back on their feet.

WFP is working tirelessly not only to cater to these immediate needs but also to support communities to restore their resilience and be better prepared to face new shocks,” Badejo added.

In 2021, WFP reached 5.9 million people with food and nutrition assistance, including more than 730,000 people in South Sudan who benefited from livelihoods activities, the UN agency said.

In Greater Jonglei and Unity States, where unprecedented floods and localized conflict prevented people from reaching their cultivated fields, WFP supported people with cash assistance to buy food and other basic needs, provided communities with tools to protect and maintain critical assets, and trained young people in various vocational activities, including post-harvest management.

To help communities prepare for the impact of floods, WFP built dykes in areas at risk such as Bor in Jonglei State, where constructing an 18km dyke enabled thousands of displaced families to return to their homes.

“Investing in resilience is an important step to help communities find their way out of poverty and hunger,” Badejo said. “While we stand on their side to address their most immediate challenges, we must also work closely with the government and other development partners to seek longer-term solutions to some of the chronic problems that South Sudan faces – addressing entrenched inequity and isolation and restoring conditions for peace and stability.”

The statement said that contributing to alleviating South Sudan’s hunger crisis in an integrated and sustainable way is a significant challenge.

“WFP faces a major funding shortfall of US$526 million for the next six months to cover its crisis response, resilience building, and longer-term development programs in the country,” the press statement concluded.