The UN Panel of Experts on Sudan, in its final report to the Security Council, stated that the Rapid Support Forces’ quick advance and taking of large swathes of the territory in the Darfur region was a result of opening supply routes through South Sudan and complex financial networks.

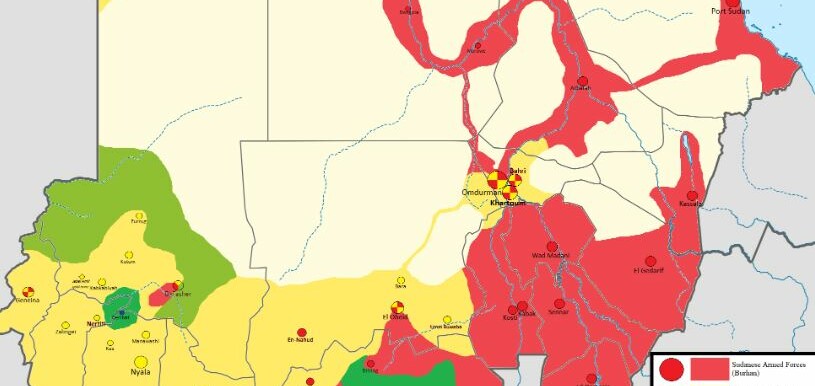

According to the report, by mid-December 2023, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) had secured control of four of five Darfur states, including strategic cities, supply routes, and border areas.

“RSF captured Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) headquarters in South Darfur (Nyala on 26 October), Central Darfur (Zalingei on 31 October), West Darfur (Ardamatta on 4 November) and East Darfur (Ed Daein on 22 November)” the report reads in part. “The operation was supervised by Abdelrahim Dagalo (RSF deputy commander-in-chief). During the first phase of the conflict (April to July 2023), RSF seized large parts of Darfur, including important SAF bases in localities such as Kutum, Kabkabiyah (North Darfur) and Am Dafok (South Darfur). SAF retained a presence only in North Darfur State, in particular its headquarters in El Fasher, which RSF refrained from attacking after informal negotiations with the Darfurian armed movements there.”

The report says the RSF takeover of Darfur relied on three lines of support: the Arab allied communities; dynamic and complex financial networks; and new military supply lines running through Chad, Libya, and South Sudan.

“While both SAF and RSF engaged in widespread recruitment drives across Darfur from late 2022 onwards, RSF was more successful. It harnessed substantial support among Arab communities, in particular in South and West Darfur. The war crystallized a feeling of common Arab identity among Arab communities of Darfur (and Kordofan), temporarily suspending old internal rivalries. Native leaders were further motivated by the RSF offerings of cars, money, and military ranks. The Arab communities provided RSF with the human resources and local knowledge crucial to quickly capture the main cities and supply routes across Darfur,” the UN experts observed. “Complex financial networks established by RSF before and during the war enabled it to acquire weapons, pay salaries, fund media campaigns, and lobby and buy the support of other political and armed groups. RSF invested large proceeds from its pre-war gold business in several industries, creating a network of as many as 50 companies. RSF senior members and their associates owned and controlled several of those companies in the region. Al Khaleej Bank became instrumental in financing RSF, receiving a USD 50 million transfer from the Central Bank of Sudan in March 2023.”

“With that money, the RSF developed new supply lines of military equipment and fuel through eastern Chad, Libya, and South Sudan,” the report added.

From July onwards, RSF deployed several types of heavy and or sophisticated weapons, including unmanned combat aerial vehicles, howitzers, multiple-rocket launchers, and anti-aircraft weapons such as man-portable air defense systems. This new RSF firepower had a massive impact on the balance of forces, both in Darfur and other regions of the Sudan. New heavy artillery enabled RSF to swiftly take over Nyala and El Geneina, while its new antiaircraft devices helped to counter the main asset of SAF, namely, its air force.

However, as the RSF advanced, according to the experts, violence against civilians swept through Darfur. In West Darfur (El Geneina, Sirba, Murne, and Masteri), RSF and allied militias targeted the Masalit community in particular.

“RSF allied militias systematically violated international humanitarian law. Some of those violations may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. RSF and allied militias targeted gathering sites for internally displaced persons, civilian neighborhoods, and medical facilities and committed sexual violence against women and girls,” the report noted. “In El Geneina alone, between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed. SAF not only was unable to protect civilians but also used aerial bombing and heavy shelling in urban areas in El Fasher, Nyala, and Ed Daein. That action by the warring parties caused a large-scale humanitarian crisis.”

Meanwhile, SAF could not replenish its Darfur garrisons with any meaningful military supplies, given that RSF had taken control of most portions of the road between Kusti and El Fasher, the main supply route of SAF from Khartoum and Port Sudan.

In the meantime, pressure on the Darfurian armed movements to side with either SAF or RSF triggered divisions among and within the movements. While most armed movements initially publicly adopted a position of neutrality, that stance changed dramatically on 16 November 2023, when several key leaders of armed movements, including Minni Minawi (Chair of the Sudan Liberation Army-Minni Minawi) and Gibril Ibrahim (Justice and Equality Movement Chair) declared their support for SAF.

However, the fragmentation within movements was yet to have any effect because forces on the ground refused to join the fighting.

While Darfur was experiencing its worst violence since 2005, various regional and international actors attempted to mediate between RSF and SAF. The combination of an excess of mediation tracks, the entrenched positions of the warring parties, and competing regional interests meant that those peace efforts had yet to stop the war, resulting in a political settlement, or address the humanitarian crisis.