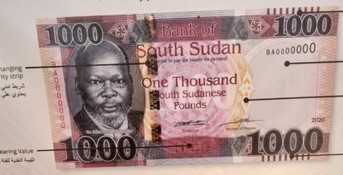

South Sudan has announced the introduction of a new banknote with a larger denomination to cope with hyperinflation which shows no signs of slowing.

At a press conference in Juba Tuesday morning, Central Bank Governor Dier Tong Ngor said a new Pound bill of 1000 will start to circulate as a way to make transactions more efficient.

Until now, the biggest denomination in the country was 500 South Sudanese Pounds.

The bank governor said the move to introduce the new Pound bill of 1000 aims to mitigate runaway inflation and a perpetual depreciation of the currency which has eroded the face value currency in the recent past.

“As you are aware, the past few years have been characterized by high inflation and a perpetual depreciation of the currency which has eroded the face value of our banknotes. Bank of South Sudan carries out a review of denomination mix from time to time to ensure that the available denomination mixes are aligned with the macroeconomic conditions and the demands,” he explained.

He pointed out that international best practice requires that central banks review their currency regimes at intervals of five to ten years to ensure that the demand for banknotes is well aligned with economic activity and address weaknesses and challenges associated with the management of notes and coins in circulation.

“Much thinking went into the decision to introduce the SSP 1000 denomination banknote. In doing this, we aim to align the structure of the banknotes with the needs of the people who use them for their daily transactions. We need banknotes that are convenient and that are of high quality and security and also cost-effective,” the central bank boss said.

“Accordingly, in July 2019 the Bank of South Sudan planned to introduce the SSP 1000 after the successful introduction of the SSP 500 banknote in 2018 which showed to us the significant increase in the demand for the higher denomination of banknotes,” he added. “It is in this view of the need to make our currency more convenient that we are today introducing the 1000 SSP banknote into circulation to complement the existing banknotes. And as I said earlier, to ensure customer convenience and bring about efficiency in the printing of currency and to generate saving for the country.”

He said the introduction of this 'high-value' note should not be misinterpreted to mean a shift away from the central bank policy of promoting the use of electronic payments.

“While vigorously pursuing financial inclusion by accelerating the migration to e-payments platforms, we are also mindful of the relevance of cash in our day-to-day lives and dealings. Undeniably, cash is still king and preferred medium of payment by the large and formal sector in our economy,” Dier Tong explained.

“This is why we continue to pay attention to enhancement in the structure, security, features, and management of cash within the economy. In the coming days the Bank of South Sudan will embark on a nation-wide campaign to educate the general public on the key security features of the new denomination,” he added.

Tong said banknotes are very expensive for the central bank to print and that printing small notes costs a lot of foreign currency every year.

“This one will reduce that significantly. The other justification is storage. Storage has been a challenge to us because we have these small denominations and you need massive space to store these small currencies. This one will change with the introduction of the new currency,” the central bank governor explained.

Reacting to this move, Professor Abraham Matoc, an eminent South Sudanese economist, slammed the decision made by the central bank and said it would only make things worse.

“First of all, if they have released a 1000 SSP banknote then it means our currency is not doing well because when you compare with other countries, you will see that their biggest currency banknote denomination is 100. And their money and economies are strong. Take for example the US $ 100 and 100 Sterling Pounds of the United Kingdom and 100 Euros, you will find that their currencies are stable and their economies are strong,” Prof. Matoc told Radio Tamazuj.

He said that any country with large banknote denominations like South Sudan with 500 SSP and now 1000 SSP, cannot withstand shocks to the market and that it will automatically lead to hyperinflation.

“There will be a lot of money in circulation chasing few goods. In other words, too much money in hands and few goods to purchase which leads to a situation of inflation,” he added. “Maybe they carried out their studies which informed their decision, but according to me, this thing is not economically healthy. It will affect our economy and it will collapse very seriously. There will be hyperinflation and inflation plus the black market which is existing now, the economy will decline.

Asked what should have been done, Prof. Matoc said, “If we are thinking in terms of economics, we should ensure that the highest banknote is SSP 100 and then 50, 25, 20 SSP and we should have coins. Now we do not have coins in our market. It is very dangerous for the economy.”

He asked, “The SSP 500 banknotes are not available in the market. Where did they go? So where will the SSP 1000 banknote go? These big denominations encourage and support the hoarding of money. The people will keep their money in their homes and it is not healthy at all. I disagree with it.”

He advised that the right thing to do is to encourage investment and make investors create industries that will also create jobs and that will encourage production, “then there will be jobs created and there will be wealth in the hands of the people and the money will be circulating in the market. That is the only solution.”

Last November, Central bank governor Dier Tong announced that the monetary institution was increasing its interest rate to 15 percent, the cash ratio to 20 percent, and also introduced treasury bills to manage liquidity as some of the measures taken to address runaway inflation in the country.

At that time, an economic analyst, Professor Akim Ajieth Buny, said the raft of policy interventions announced by the newly appointed governor of the Bank of South Sudan will have little or no impact in salvaging the economic cringe the country is grappling with.

“It is completely ambiguous, and it is very difficult to know what they mean because in this country the interest rate does not work. We don’t have a housing market. It would work if we had a housing market because this is where you can increase the interest rate so that people who are buying houses or taking loans will have to pay something bigger and this is where the government will get something in return,” Prof. Akim said then.