A member of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan has said that it is of paramount importance for the Government of South Sudan to set up and operationalize the Hybrid Court prescribed in the 2018 revitalized peace agreement. He contends that the commitment to set up the court remains unfulfilled but it is an important one as it would play a pivotal role in trying instigators and those who design, plan, and assist in the commission of crimes.

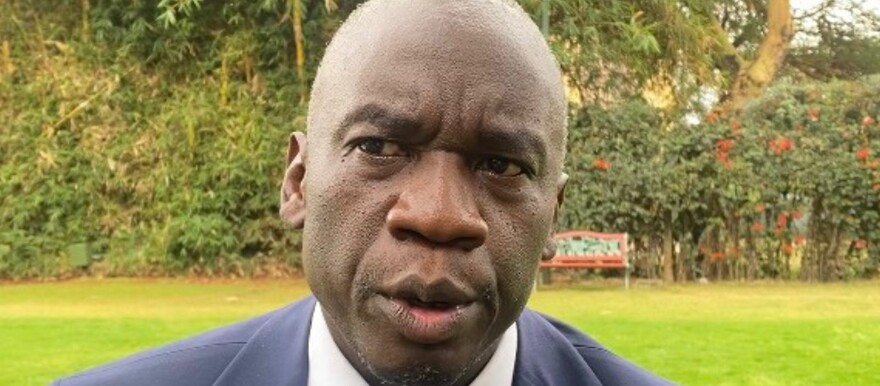

Commissioner Berney Afako, a Ugandan lawyer with experience in conflict mediation, has worked in the fields of human rights, refugee law, criminal justice, and transitional justice in several countries and serves as a member of the Council-mandated body charged with monitoring and assessing the human rights situation in South Sudan together Yasmin Sooka and Carlos Castresana Fernandez.

Radio Tamazuj caught up with him last Thursday during the launch of the Commission’s latest report titled “Entrenched repression: systematic curtailment of the democratic and civic space in South Sudan,” and sounded him out about a wide range of human rights issues in South Sudan.

Below are edited excerpts:

Q: Commissioner Afako, you recently released a report about human rights violations in South Sudan. Could you tell us more about that and the new report?

A: We started to plan our next report after we reported to the United Nations Human Rights Council in March. Every year we produce a mandate report that paints a picture of the overall human rights situation in the country but in between, we also produce what is called conference room papers which pick up a theme. The reason we selected this theme of democratic and civic space is that South Sudan is going into a very critical phase of the transition where it is anticipated that South Sudanese would have the opportunity to make a new constitution and based on that constitution, they would go to elections.

Of course, the preparation for the elections has already started with some of the political parties beginning to mobilize and organize. It is very important that these processes, particularly the elections, are carried out in a way that does not trigger tensions and violence but is carried out in an environment in which South Sudanese, aspiring leaders, and political parties can organize freely so that the freedoms of information, of opinion, of expression, of assembly, of movement which are core civil and political rights are respected so the core right of the citizen to participate in choosing the leaders, in defining the social contract with the state, is respected.

Q: There have been many other reports before this report especially on killings, torture, sexual violence, and targeted ethnic cleansing at some point. What has the response of the government been?

A: About previous reports, what we do is gather the material, and evidence, write it in a report, share it with the government, and publish it. We continue having a conversation with the government around the issues that are raised and others too based on our findings. Because we are set up by the Human Rights Council, which is a body of states, states from around the world are elected into the Human Rights Council and they oversee the status of human rights in specific countries. They highlight a particular country which might need bodies like ours and South Sudan is one of them.

The reason for that is that the international community recognizes that South Sudan was in a really difficult transition, particularly after the conflict of 2013 and the signing of the 2015 peace agreement allowed the international community to focus on human rights to address the drivers of the conflict among other things so that you would have a dispensation after the transition which would be more democratic. So, that is why we have come back to this question of democratic space because it is the logic of the transition period that it must culminate in the choice of the South Sudanese people based on a legal text, a fundamental legal document that they have helped to define.

Q: Commissioner Afako, based on your assessment, has there been an indication of improvement in human rights conditions in South Sudan?

A: You see, human rights are general, they range from civil political rights to social and economic rights et cetera. So, it is very difficult to make a generalized statement but what we have done with this report is to take the experience of civil society and the media as barometers. They are like a litmus test. We look at what happens to civil society, can they meet freely? Can they engage, criticize, and hold the government accountable? For the media, can they report things as they find them? The media is there to assist citizens with information so that citizens can make informed choices about politics, about social life. But we are seeing what we are calling an entrenched repression, the closing down of space, the media does not function, never mind the laws that permit them to do so, the practice is restrictive.

So, we say in this report that regarding the question of democratic space, for the media, and civil society, South Sudan is not making progress. We are saying it is time to address this because we are now entering into a phase of the transition where views must be respected. People might have different views on the form of government and on the powers that the president or governors should wield. Of course, that is politics, yes, but they are entitled to have a robust debate and even disagree with proposals that come from the government.

In the end, let there be a system for making the choice and then they will accept the result because they have been heard fairly. If you do not have that, then you have grievances, and then it begins to fuel the sort of disaffection that has translated into violence for too long.

Q: Is there any evidence that officials in the government who have committed atrocities and or perpetrated war crimes will be prosecuted?

A: I think much more can be done. We had hoped that the government would cooperate with the African Union and establish a Hybrid Court. The Hybrid Court is not an imposition from outside of South Sudan, it is a decision of the negotiators including people who are now in government and others. They said that after 2013, given what we saw and given the status of our institutions and how divided and polarized we are, we think we need to have a partnership for justice, a partnership between South Sudan and other Africans but not opened internationally. People who would understand the culture, and political context here, to sit together with them as judges, investigators, and prosecutors to make sure that the victims of that violence receive justice.

That commitment remains unfulfilled but it is an important one. South Sudan said it is better to start with a truth commission. But you see, these institutions are complementary because what emerges in the truth commission will show that some crimes have been committed but what happens to the perpetrators? That is why you need a Hybrid Court, not for everybody, but for the handful or so of people who were the instigators. They may not have been carrying guns and pulling triggers but they design, plan, and assist in the commission of crimes. That is why it is important and the importance of accountability is that it is a way of reinforcing the values of the country and the community.

You prosecute those people who carry out extrajudicial killings, murders, attacks on civilians, and mass rape because that is a way of signaling that this conduct is against our values, culture, and interests. So, that represents your statement of who you are. If you do not do that, there is a question mark. Are we saying that the suffering and the targeting of South Sudanese and the attacks on the women are part of South Sudanese culture? It is not. So, we have to refute that with accountability and we have to also strengthen the domestic justice system.

Over the last few years, we have been engaging with the Ministry of Defense and the military and encouraging them to make sure that all military courts function. In some cases, they have been doing better on that front in Equatoria and others but we want to see that across the justice system. We want to see the rule of law, the administration of justice well-resourced, judges being independent, and enough of them appointed, and supported by investigators and able prosecutors. So, there is a lot of work to be done on the front of accountability.

Q: This brings us to the issue of corruption because South Sudanese judges have in the past complained about poor welfare and poor remuneration. Could this be one of the reasons why the justice system is not robust?

A: I think that if you do not pay your judges, if you do not pay your prosecutors and investigators and facilitate them, then you are going to have difficulties delivering justice. Justice is like a link of chains, if one link is weak, then the whole system is weak. If your judges are not motivated, do not feel independent, are not paid sufficiently, have a paper to write on, have no vehicle to get to court to do circuits and lack resources, then you are not going to have the delivery of justice. So, it needs a holistic approach, it needs investment. If you neglect the justice sector, then you cannot expect to have the rule of law and accountability.

So, in our engagement with the government, in our recommendations, we are saying that do not forget justice. The resources should not only go to particular sectors whether it is security or the economy. The justice sector is important and this is also why South Sudanese need to articulate these in a new constitution which says an independent judiciary is important. A constitution that protects the salaries, the resourcing, the appointment systems, and the removal systems of judges so that they cannot be removed by the executive because they might not like some of the decisions.

The same for human rights. We are here as a body established in Geneva but tomorrow want to see an independent and credible South Sudanese Human Rights Commission where commissioners are appointed in ways that are independent and transparent, serve their term, hand over to others, and their findings are respected and there is a legal obligation to implement them.

Q: There is the issue of the proliferation of armed militia groups under opposition groups and even the government who do not read your and other reports about rights abuses. What is your Commission going to do to ensure they internalize these reports and that they need to be part of the accountability process?

A: What we tend to do principally is when we publish our report, we will make it available digitally, now this report that we produced is already online. Anybody can access it. We do not have a very strong outreach capacity to promote our product. We ordinarily would rely on the free media to do that and that is why we keep coming back to this point. The absence of a media that can speak to explain our reports in South Sudan is holding back human rights. If you infringe on one human right, it has knock-on effects. So, one of the effects of this is that some of the human rights reporting, some of the engagement is limited because the space to do that for people like yourselves to carry these reports, discuss them on local radios in the different states, we are not seeing.

So, we need to do more. We try to do this by engaging the government as often as we can, but we cannot do it all the time. We are not full-time, we are not based in Juba, and our staff continue to do that but at the higher levels, we only have a handful of opportunities in the year to do that. So, we hope that the quality of our reports carries it, and we hope that it is shared widely as possible, but we will wait and see and we will continue to carry out our mandate, we will continue to look at new issues, we will be reporting on more issues. This is our first report on this question of democratic and civic space and we want to follow this for as long as our mandate allows because as we get to December 2024 we must conclude the transition period credibly.

Q: Is the commission mandated to set up a local tribunal that can try the crimes that have been committed in the country?

A: That is squarely the responsibility of the government and the state must hold people accountable. When it does not do that then it is failing those core obligations. We have been stressing the importance of the Hybrid Court, we have been stressing the importance of a strong justice sector, particularly the criminal justice sector, including military justice so that there is accountability.

We do not have the mandate, resources, or capability of doing that but what we do is encourage the government to undertake this and in other cases, institutions like the UNMISS have been assisting with other countries through mobile courts and the sexual gender-based violence special courts. Those are all efforts by others to assist because South Sudan is still undergoing an intensive state-building process. Not all these are in place but available resources must be used responsibly and allocated for addressing these important questions.

Q: Is the issue of nonpayment or delayed salaries for the armed forces and civil servants a contributory factor to rights abuses?

A: We have previously reported on the question of salaries not being paid for soldiers, particularly the lower ranks, and we were saying that this was contributing to some of the predation around their camps and encouraging that they be paid sufficiently and promptly. But we say that the fundamental problem is that of leadership and the doctrine of the military. Is there is there tolerance or intolerance for violations? It is important that South Sudan’s leadership, both civilian and military, build that culture of intolerance (for violation) and that it is explained to soldiers what is expected of them and that when they carry the gun, they do so on behalf of the citizens. They are not to point it at the citizen and that is a fundamental cultural shift that they have to undergo. We are encouraged by the provisions of the peace agreement which say that you are going to have security arrangements, rebuild the army and security services into protectors of citizens. So, we are saying that this is important, including for the National Security Service (NSS) Bill going through the assembly. You have to remove excessive powers so that they cannot just pick up people, and arrest and detain them.

Q: Commissioner Afako, as we conclude, what are your recommendations to the Government of South Sudan in terms of ending the prevalent rights abuses in the country?

A: Let me focus on our report which is about democratic space particularly because of these important processes of constitution-making and elections. The recommendations are, first of all, to stop restricting the space of civil society, media, and political actors as they go into this phase. Change it permanently so that South Sudan is a society that is expressive of the diversity of its people and their views and that does not undermine the position of the government but strengthens the credibility of government.

When you have a free society, and a free press, when civil actors can engage, then they can contribute to get the best out of your people. So, these violations are counterproductive but they need to be recognized and changed and then it will be manifested in the way that they oversee the security services, oversee the army, and hold the governors accountable for what happens in the states so that nobody in South Sudan is a law unto themselves.