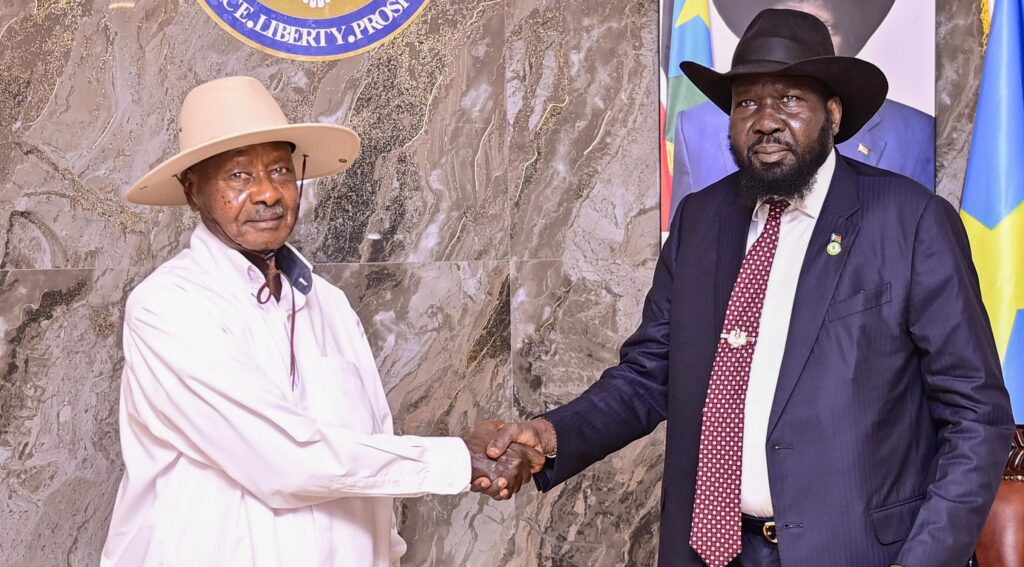

The world’s youngest nation, South Sudan, finds itself at a crossroads as it navigates complex bilateral relations with its neighbor, Uganda. The two countries share historical bonds marked by cultural ties and divergent political interests—factors that could significantly affect their stability, as well as that of the region, and hinder economic development.

During South Sudan’s decades-long struggle for independence, which culminated on July 9, 2011, Uganda was a key supporter, providing military and logistical assistance. Ugandan troops, under President Yoweri Museveni’s leadership, fought alongside the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) against the Sudanese government. However, this support was often framed as part of the campaign against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), which was battling the Ugandan government.

Since independence, relations between the two nations have been shaped by both cooperation and competition. South Sudan became a ready market for Uganda’s industrial products and labor force, while Uganda played a vital role in supporting peace processes, particularly through regional bodies like the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). Additionally, Uganda has provided crucial trade links, facilitating the flow of goods into landlocked South Sudan.

However, the dynamics have not always been smooth. Uganda’s military involvement in South Sudan remains contentious, especially after the civil war erupted in December 2013. The Ugandan People’s Defense Force (UPDF) was deployed to support President Salva Kiir’s government against the opposition led by then-Vice President Riek Machar. This intervention exacerbated political and military tensions, not only between the two countries but also among factions within South Sudan, resulting in significant loss of life and destruction of property. Infrastructure damage and disruptions to humanitarian services—particularly in conflict-ravaged regions like Nasir, Greater Yei River County, and parts of Central Equatoria—have taken a heavy toll, displacing thousands and creating waves of refugees. Tribal conflicts have also intensified, forcing many to flee across borders into refugee camps.

Although South Sudan’s internal conflict officially ended with the 2018 peace agreement, the country remains fragmented, grappling with fragile governance and a worsening humanitarian crisis. Consequently, relations with Uganda are no longer simply a matter of friendship or enmity; they are now deeply intertwined with regional geopolitics, as evidenced by both nations’ interventions in neighboring countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Somalia. These interventions have frequently violated international humanitarian law and arms protocols.

Uganda’s support for President Kiir has had far-reaching implications for South Sudan’s domestic politics. Opposition groups, including those aligned with Machar, have accused Uganda of bias, arguing that its involvement has deepened internal divisions. This intervention has also drawn South Sudan into a broader regional power struggle, with countries like Sudan and Ethiopia backing various opposition factions.

The competition for influence extends beyond politics into the economic sphere. The two nations share a border critical for trade and energy supply. Uganda has developed robust infrastructure, including oil pipelines that may eventually link South Sudan’s oil reserves to Ugandan markets. Cross-border roads could further facilitate Ugandan exports, solidifying its role as a key trading partner. However, as both countries vie for control over resources, tensions are likely to escalate.

Uganda’s involvement in South Sudan’s oil sector has also attracted international scrutiny. Kampala has sought strategic investments in South Sudan’s oil industry, capitalizing on the latter’s rich reserves but inadequate infrastructure due to ongoing instability. In this context, both nations must work to prevent disputes that could undermine mutual interests.

South Sudan’s strategic location in the Horn of Africa makes it a valuable partner for global actors. Its relations with Sudan, Ethiopia, and Kenya influence its foreign policy, while external powers like the U.S., China, and Russia compete for influence, drawn by the region’s untapped natural resources.

Uganda, as one of East Africa’s most stable and influential nations, has a vested interest in South Sudan’s stability—not only to secure its borders but also to maintain its regional dominance. However, its close ties with Kiir’s government have drawn criticism from neighbors like Sudan, which has its own fraught history with South Sudan and has occasionally supported rebel factions, further complicating bilateral relations.

International organizations, including the United Nations and the African Union, have also shaped Uganda’s approach. Kampala has used these platforms to advance its interests while navigating pressure for greater regional cooperation and conflict resolution. The global community continues urging Uganda to adopt a more neutral stance in South Sudan, promoting dialogue among all factions.

To navigate its relationship with Uganda, South Sudan needs a clear diplomatic roadmap—a foreign policy that balances economic and military dependence on Uganda with the protection of its sovereignty and internal stability across all 64 ethnic communities. The government must avoid overreliance on any single nation, particularly Uganda, lest it become entangled in external conflicts.

South Sudanese leaders should continue engaging with Uganda while diversifying international partnerships. Strengthening ties with regional powers like Ethiopia and Kenya, underpinned by clear protocols, could foster a more balanced foreign policy. Most critically, South Sudan must address its governance challenges to reduce foreign interference in its domestic affairs.

With a weak governance system, South Sudan’s sovereignty remains vulnerable to external influence. Only through inclusive governance and genuine peacebuilding can the nation free itself from the crossfire of regional politics.

The author, Mogga Loyo Junior, can be reached at mogtomloyo@yahoo.co.uk.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.