Sudan needs a national security strategy to guide the reforms of its security sector from a tool of repression to sustain the old regime to a professional force that protects citizens under a democratic system.

Peace Agreement: A Glimmer of Hope

Since the ousting of the government of Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, Sudan has been struggling to uproot the ills of 30 years of repressive rule, the co-opting of state institutions by the National Islamic Front, and the politicization of the security sector. The joint civil-military transitional government has been struggling to live up to the slogans of the Sudanese revolution—freedom, justice, and peace—as well as meeting the daily basic livelihood needs of the citizens. These competing priorities have been exacerbated by the spread of COVID-19, unprecedented rainfall and flooding along the Nile, fraught civil-military relations, and years of accumulated government debt. Given the uphill tasks of dismantling the well-entrenched structures of the defunct regime while improving day-to-day living conditions, the success of the transition is far from assured.

One glimmer of hope is the October 3, 2020, Peace Agreement that seeks to end the long-simmering civil conflicts in the west and south of Sudan. While important actors still need to be brought in and details worked out, this Agreement provides an important opportunity for advancing the democratic transition absent active conflict. With the mandate to integrate the armed opposition into the security forces, the Agreement also necessitates a vision and plan for what a renewed security sector in Sudan will look like.

Security Sector: A Challenge for the Transition

The choices made in addressing the priorities, pace, and sequencing of any political transition will shape the degree to which it will effectively bridge the dismantling of an old authoritarian regime with the establishment of a new democratic system. This is especially the case for the security sector as it must transition from a tool of repression to sustain the old regime to one that protects citizens under a democracy. In the case of Sudan, a number of issues shaping the reform of the security sector bear special consideration:

Reform and Integration. The security sector created by the Bashir regime is highly fragmented and exceptionally large. It comprises an estimated 277,000 personnel, not including the various affiliated armed groups. Many of these units are viewed as unprofessional. Furthermore, while down from their peak during the long civil war with South Sudan, military expenditures still account for nearly 10 percent of the national budget, and the army is heavily involved with other parts of the economy.

Compounding this challenge, the armed movements that have been fighting the government, which are also characterized by poorly trained and undisciplined soldiers, will now need to be integrated into this security sector. The number of fighters to be integrated, moreover, has been left for the joint military institutions to decide. Absent from this process is an overarching vision or strategic guidance on the size, structure, capabilities, and objectives of this new security sector.

Reforming the Sudanese security sector while bringing together disparate security actors into a single national entity requires time as well as new thinking. This includes changing the mindset of how security is perceived, planned, managed, and delivered to the Sudanese people. Moving forward without such strategic direction can cause the entire reform process to easily unravel.

“In a democracy, civilians have a vital role in setting the vision and strategic policy of the security sector.”

Understanding and Sequencing. Both the Constitutional Charter and the Peace Agreement narrowly define security to include only those in uniform. In its Article 8.12, moreover, the Constitutional Charter designates the military as the actor responsible for transforming military institutions. In addition to asking the military to reform itself, this approach overlooks the fact that in a democracy, civilians have a vital role in setting the vision and strategic policy of the security sector. Likewise, members of parliament and civil society have important oversight functions. Within government, moreover, the justice sector, finance, immigration, customs, and other ministries have a role in ensuring the security of the population.

The sequencing of the phases of the security transition in the Peace Agreement also introduces challenges. For example, the plan for transforming, developing, and modernizing the security sector is in the final (fourth) phase, while disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) is to be implemented in phase three. In other words, the sizing and reform of the new armed forces is designated to occur without any strategic guidance.

Representation and Professionalism. One of the challenges in the post-conflict transition is how to reconcile representation and professionalism in the security sector. In most civil war contexts, certain ethnic groups dominate the armed factions, and they tend to be overrepresented in the transitional government, which rewards those with guns, as in the case of South Sudan. This domination, coupled with poor training, has resulted in the creation of a gun class that controls the political marketplace that makes South Sudan susceptible to political instability.

Although the Sudan Peace Agreement emphasizes building a professional national army based on merits and guided by new doctrine, it isn’t clear how this doctrine is to be developed. Nor is there a plan for remediating the educational gaps—at both the noncommissioned officer and officer levels—of the standing army or the members of the armed movements to be integrated.

The DDR Process. The demilitarization of armed groups is a critical process for transforming the security sector and transitioning from war to peace. However, the Sudanese have adopted a conventional approach to the DDR process that has consistently been shown to be ineffective for complex conflicts typified by multiple armed actors, loose command and control structures, ethnic rather than national loyalties, and ambiguity over who is a fighter. Such complexity defines the reality in Sudan. The DDR process has been approached as a technical military activity rather than an integral part of the political process of security sector transformation. This is reflected in that the entire DDR process is entrusted to a state-based commission, which in addition to lacking representation, is itself subject to corruption.

The lack of clear criteria specifying who qualifies as a soldier (and therefore, who may be integrated into the national army or receive a payout to demobilize) also opens the process to corruption, rigging, new recruitment, and over-reporting. The task of managing these arrangements with the varied armed movements currently active in Sudan will pose a real challenge for coordination and risks duplication unless it is nested within the overarching security strategy.

Lessons Sudan Can Adapt from Other Transitions

While Sudan will have to adapt to its unique situation, there is much it can learn from the experiences of other countries who have undertaken reforms of their security sectors during democratic transitions. Some relevant lessons from these experiences include:

DDR is Not a Standalone Activity. DDR is part of a larger political process to reform the security sector. In the absence of a national vision, grand security strategy, and political leadership with command and control over the respective forces, DDR initiatives are likely to fail. Integration of rival forces for political expediency, for example, is often problematic unless it is guided by a national strategy for building a genuinely professional security sector.

DDR initiatives benefit greatly from some form of a national security strategy that defines the threats a country faces and the force structure needed to provide for such security. As a national security strategy takes time to create, some elements of DDR may need to begin simultaneous with a national security strategy process. However, even this should be guided by an initial vision articulated by civilian leadership.

Contextualizing the DDR Process. The complex nature of security in Sudan, where there are not just two rival factions but more than a dozen armed groups, necessitates tailoring the concept of DDR to its unique reality. When South Sudan attempted to apply a standard DDR framework, for example, it proved problematic as there was not a strong foundation in the army on which to build. Rather, government forces often resembled an armed, ethnic militia rather than a professional military. The subsequent DDR integration resulted in an even less unified and accountable security force. In Sudan, as the 30 years of Islamic party rule has supplanted traditional military professionalism with its own doctrine and ideology, the starting point for transforming the security sector will require some fundamental reorientation.

DDR Not a Seamless Concept. It often goes unrecognized that the components of DDR are very different, with each requiring different skill sets and expertise. Disarmament and demobilization (DD), specifically, require security actors to oversee the identification and decommissioning of combatants and assets over a discrete time period. Reintegration, in contrast, is a developmental and peacebuilding process involving close cooperation with communities over an extended period of time. Nor are these sequential processes, as is often assumed in conventional DDR. In fact, in complex contexts like Sudan, experience shows that the community reintegration process is particularly vital for avoiding recidivism and should be implemented from the outset. Since the Sudan Peace Agreement currently treats DDR as a singular concept, this process requires further conceptualization and adaptation.

“Experience … highlights the importance of an inclusive and participatory security review process through the broad-based engagement of citizens.”

The Political Economy of DDR. The experience from many African countries shows that the behavior and interests of powerbrokers or warlords rather than individual ex-combatants typically pose the greatest challenges to effective DDR processes. Given the potential flow of resources to the DDR program, these powerbrokers will have an incentive to control such resources, benefiting themselves financially or empowering their own faction. Influence over decisions such as which armed groups are to be disarmed and who may join a national security forces will also have direct implications for power dynamics in Sudan.

Broad Engagement with Citizens. For the security sector review process more generally, experience from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Burundi highlights the importance of an inclusive and participatory security review process through the broad-based engagement of citizens. Such a process ensures a broader representation of interests, popular support, and societal legitimacy of the process, which can then be used to reorient policy priorities. It also deters elites from hijacking the process and creates the necessary pressure for change in the security sector that leaders cannot easily skirt.

In Sierra Leone, media and civil society played a critical role in fostering the national dialogue on security. The legislature can play an important role in the security sector transformation process if their technical capacity and understanding of their oversight role vis-à-vis the security sector are enhanced. Local government and traditional leaders may also bring community support and broader representation to the process. In short, the process of security sector review and transformation are often as important as the outcomes they generate.

Moving Ahead

Sudan is passing through an extremely difficult and momentous transition, yet with enormous opportunities to realize the principles of the Sudanese revolution: freedom, peace, and justice. The institutional control created by the Islamic regime is more pronounced in the security sector than in virtually any other segment of Sudanese society. This makes the reform of the security sector not only a top priority but one of the most effective ways of undoing the 30 years of predatory rule by the Bashir regime.

“Reform of the security sector [is] … one of the most effective ways of undoing the 30 years of predatory rule by the Bashir regime.”

The Peace Agreement entrusts the National Security and Defense Council to provide a grand plan for the transformation, development, and modernization of the security sector. The Agreement also identifies the transformation of the security sector as a priority agenda for the upcoming Constitutional Conference. Similarly, the Sovereign Council, the cabinet, and Forces for Freedom and Change have resolved to develop a national security strategy as one of the urgent tasks of the transitional period. Despite these high-level commitments, Sudan’s transition process lacks an overarching framework to guide the reform of the security sector. Following are some actions that can be taken to establish such a guiding framework:

Security Sector Review. Understanding the status in terms of size, skills, and level of professional damage to the security sector caused by the Islamic regime should be the starting point for any reform. Constructing and deconstructing the problem through an inclusive and participatory review process is key for finding a nationally owned solution.

Commonly Shared National Vision. Although the Sudanese revolution has provided clear slogans for the transition, there is a need for these principles to be articulated in a commonly agreed national vision to be adopted during the Constitutional Conference. This vision will guide all the reforms during the transition, particularly in the security sector.

National Security Strategy Development. Simultaneous to the security sector review, a national security strategy development process can be initiated in order to:

- Identify key security threats facing Sudan and security needs

- Articulate a national security vision for Sudan

- Establish the purpose and objectives of Sudan’s national security structure

- Designate the division of labor between the military and other security entities

- Determine the size, force requirements, and recruitment criteria for the security sector

Initiating such a national security strategy process will provide the basis for not only determining the forces to be demobilized from the current security sector and armed movements through DDR, but also for guiding the process of integrating the various armed movements into the reformed security sector. This national security strategy process will also provide a new doctrine that would instil a national identity, ethos, and command and control structure that can avoid a fractured security apparatus that will only serve parochial interests.

- Be Mindful of the Political Economy of DDR. Experience shows that without proper oversights, DDR is perceived by security and political actors as a revenue-generation and employment opportunity for armed groups. This will make the DDR process susceptible to corruption and rigging, while further empowering the most politicized security actors.

- Establish People-Centered Security. Security is a public service like education and health. The way security is perceived, planned, managed, and delivered needs to involve citizens and not only the uniformed security services.

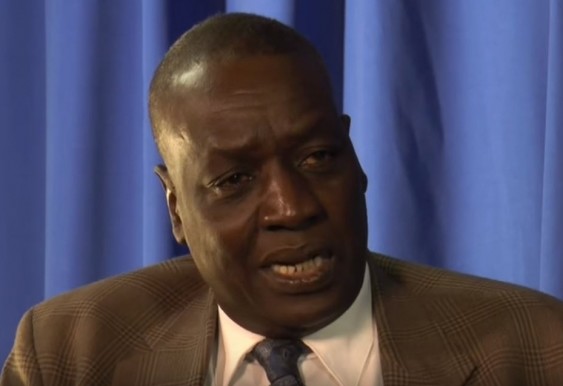

Dr. Luka Biong Deng Kuol is a Global Fellow at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made are the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.