South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, often appears in headlines as a land afflicted by endless conflict, insecurity, power struggles, wealth inequality, greedy and irreconcilable warlords, and humanitarian crises. Yet, these challenges did not spontaneously arise in 2013, nor can they be reduced to a struggle between opposing factions.

At the root of the endless conflicts in South Sudan is that it does not exist outside the law. It is a hurt, hurting and hurtful community of strangers forced together by history and nature without formally agreeing on how to co-exist. In other words, it is a nation shaped by a legacy of conquest, colonialism, settler colonialism, and internal fractures that have never been collectively addressed. To foster a sustainable peace, South Sudan must embark on a journey of re-membering—a process of piecing back together all that has been torn asunder, honestly confronting its historical wrongs, and charting a new path grounded in justice, truth-telling, and healing.

This brief piece seeks to reaffirm a longstanding argument championed by countless South Sudanese voices: there is no shortcut to achieving lasting peace in South Sudan.

The article is divided into three parts: (I) Why the root cause of the South Sudan problem is historical, (II) Why and how it is important to address these historical wrongs, and (III) Recommendations—including convening leadership dialogue leading to national dialogues and culminating in a new social contract for peaceful co-existing, statecraft, and governance.

I. Why the root cause of the South Sudan problem is historical

South Sudanese were set up by history to fail, be divided, underdeveloped by generations of conquerors, conquest, colonialism, and settler-colonialism that dehumanised, separated, and underdeveloped communities. From the era of the Turko-Egyptian conquests in the 19th century to the subsequent British colonial rule, outside powers extracted resources and labour from the region with scant regard for its well-being, cultural, spiritual, and cosmological foundations of the sustainable development of its people. The forceful and disrespectful amalgamation of diverse ethnic groups under a single colonial administrative entity sowed seeds of entrenched division, distrust and destructive competition. The British practised indirect rule, empowering certain groups over others; the Arabs destroyed any basis for self-rule, which cemented systems of ‘othering’ inequality and forced co-existence that sustained only a profound hatred for the coloniser and the oppressor.

The impact of these historical wrongs continues to manifest as intergenerational trauma, othering, and fractured social bonds. Decades-long civil wars—first within Sudan and later among South Sudanese themselves—intensified this trauma as communities fighting for liberation inflicted horrors upon each other, including mass murder, social re-engineering, looting, ethnic violence, and actions that dehumanised entire groups. This collective history weighs heavily upon South Sudan today, creating a cycle of pain and mistrust that fuels the conflicts.

Historically, no grand consensus ever emerged on how multiple communities within South Sudan should flourish together. When independence arrived in 2011, it did so without a comprehensive framework for social co-existence—without a shared charter for managing differences—leaving a fragile state burdened by multiple colonial legacies, deep-rooted traumas, and divided loyalties. In many ways, South Sudan still does not exist outside the law because the law itself has never fully incorporated the collective will of its diverse peoples.

II. Why and how is it important to address these historical wrongs

Re-membering South Sudan must begin with an honest assessment and truthful acknowledgement of the historical wrongs that extracted humanity and human capabilities and severed communities from their cultural, spiritual, and cosmological foundations for self-actualisation. Confronting how conquest, colonialism, and settler-colonialism systematically undermined the local social fabric, set communities at odds, and weaponised differences for the benefit of outside powers is essential. Equally important is examining the wrongs South Sudanese have done to each other. During struggles for decolonisation and liberation, many acts of violence and dehumanisation further fractured communities. Failure to recognise these internal harms perpetuates a cycle of impunity and revenge that undermines any attempt at genuine peace.

All actors in this project of underdevelopment and perpetual wars—Turk Egyptians, British, and the Sudan—must acknowledge their roles, make amends, and participate in the re-membering projects. Whether through support for reparations, transitional justice mechanisms, or investments in education and cultural revitalisation, each stakeholder has a legal and moral responsibility to help rebuild trust and re-humanise relations among communities that have suffered as a result of historical wrongs done by them. It is particularly telling—and deeply ironic—that under the provisions of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, South Sudan, rather than Sudan, was effectively mandated to provide reparations to Sudan, underscoring historical power imbalances and distorted narratives of responsibility.

Re-membering also requires an inclusive process that brings together elders, women, youth, civil society, government officials, and former combatants. Such a process must develop a shared national narrative about the suffering inflicted both by outside forces and by the South Sudanese themselves. Crucially, it must emphasise that there is only one party to these conflicts: the South Sudanese people. They are, in essence, on the same team, fighting to overcome the accumulated weight of their past—a past interwoven with intergenerational trauma and fraught with divisions. This understanding challenges simplistic perceptions of “opposing parties” or “tribal rivalries” and calls for a collective effort to transcend old wounds.

III. Recommendations: Building a social contract for peaceful co-existence, statecraft, and governance

First, South Sudan must convene a broad-based leadership dialogue that includes traditional leaders, religious leaders, political elites, women’s groups, and youth representatives. The main goal is to initiate a national truth-telling process, repair wrongs done to and by South Sudanese, ensure justice, and institute an ongoing healing process. This initial dialogue should lay the groundwork for more extensive nationwide conversations about reconciliation, accountability, forgiveness, state-building, and governance systems.

Second, national dialogues on co-existence must follow, involving communities across regions and ethnicities. These dialogues should aim to construct a shared narrative of South Sudan’s history—how external forces and internal actions have worked in tandem to dehumanise and divide the people—and discover ways to break the cycle of violence. Though painful, this truth-telling is vital in forging a collective sense of identity and repairing historical and contemporary wrongs.

Third, to give these dialogues lasting impact, the nation should enact a social contract that reconfigures how power is conceived, understood, and shared, how resources are allocated, and how justice is pursued. This compact should be rooted in broad-based, grand rules of peaceful co-existence, with structures and institutions to enforce them, ensuring that all South Sudanese feel valued and protected under the law. Closely linked to this is the need to address the deeply embedded structures of underdevelopment: a robust plan to build infrastructure, invest in social services, and integrate cultural and historical knowledge into education. Such measures can help restore the dignity and humanity that colonialism eroded.

Fourth, South Sudan must institutionalise ongoing healing and justice. Establishing transitional justice bodies, mainstreaming addressing trauma as core functions of government, and a strong judiciary are essential to investigate crimes, uphold accountability, and curb the cycle of retribution. Traditional reconciliation mechanisms, rooted in indigenous cultural practices, should also be revived to strengthen people’s trust in local forms of conflict resolution. Meanwhile, international and regional actors can offer technical support and resources but must refrain from imposing external agendas that do not align with local realities.

Finally, it is imperative to reject a “peace process first” approach, which typically presupposes that South Sudan’s problems began in 1991 or 2013 and that there are distinct parties to the conflicts. Instead, a foundational re-membering process must take precedence. Only by rewriting the social compact and refocusing national identity on shared humanity can South Sudan transform beyond contested categories and entrenched factionalism.

Conclusion

South Sudan, born from generations of conquest and colonialism, has never had the opportunity to lay down the building blocks of co-existence before being thrust into nationhood. It is a hurt, hurting and hurtful community of strangers forced together by history and nature without first agreeing on how to co-exist.

To break the cycle of violence, the nation must return to its roots by acknowledging the historical injustices that severed its peoples from their cultural, spiritual, and cosmological foundations. Through a national process of truth-telling, justice, and healing, and by creating an inclusive social contract, South Sudan can begin to re-member itself as a unified nation, committed to sustainable peace and determined to heal from its past.

Only through this deliberate journey of self-examination, accountability, and solidarity can South Sudan transform from a patchwork of adversarial communities into a cohesive, thriving nation—ultimately fulfilling the promise of independence, honouring the resilience of its people and lay the foundation for South Sudan to translate its wealthy into wellbeing.

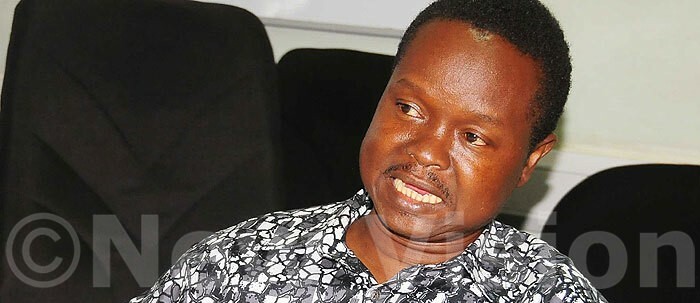

Dr. Remember Miamingi is a South Sudanese expert in governance and human rights, as well as a political commentator. He is currently based in South Africa and can be contacted via email at remember.miamingi@gmail.com

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.