The University of Juba has been a pole of stability, a bastion of higher education, and a symbol of resilience in South Sudan over the last five years. This is despite the enormous economic, security and political challenges the country has been facing since the outbreak of civil war in 2013.

Seemingly defying the downward pull of the gravity, the University of Juba has in recent years witnessed major transformation on several fronts that include, but are not limited to, improved physical environment, academic stability, rising professors and student numbers, and significant expansion in postgraduate programmes.

In fact, the number of students enrolling in undergraduate programmes alone at this premier university in March 2019 has risen to 15,000; the highest since South Sudan gained its independence in July 2011.

Growth

The number of academic staff also rose from a modest 300 in 2014 to about 600 in January 2017, before beginning to decline for reasons to be explained in this article. Postgraduate programmes have grown from about five or six programmes in 2014 to 31 programmes by March 2019; and still counting. What’s more, about 8,000 students have graduated from the university since 2015. That is an average of 2,000 graduates a year.

Generally speaking, over the same period the numbers of academic staff and students had been declining in most public universities in the rest of South Sudan, due to the lack of financial support, declining value of staff salaries and stagnant tuition fees, and political interference in the affairs of the universities.

Depreciation of national currency

However, two things in particular are hurting the University of Juba and the public tertiary education institutions most – the fixed salaries and tuition fees, both of which have been declining in real value due to depreciation of the national currency against the dollar.

The cost of operating the university as well as consumer prices have increased 3,000 fold since January 2016, while precious little has changed in the salaries received by the professors at public universities and the tuition fees paid by the students.

A medical student paid annual tuition fees of SSP5,000 in 2014 and 2015. This was worth more than US$1,500 at the official exchange rate of the time. At today’s exchange rate, SSP5,000 is worth US$18. In 2016, the University of Juba administration tripled the tuition fees so that medical students paid SSP15,000 which was worth US$200, while social science students were required to pay SSP6,000 (US$80) annually. The government intervened and cancelled the fee rise, fearing student demonstrations.

Ever since, the University of Juba has been teetering on the edge of collapse due to financial difficulties. In my capacity as vice-chancellor I sounded alarm bells, warning of the imminent collapse of the higher education sector, but they were not heeded.

In the meantime, the real value of the salaries of professors at our public universities continued to be eroded by the deteriorating exchange rate against the dollar. A recent study showed that professors in the East African region (mainly Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania) are earning an average of US$4,270 per month in real terms, while a professor at a public university in South Sudan earns the equivalent of US$136.

Massive exodus of academics

The poor pay has triggered a massive exodus of academics from the higher education sector. Over the last year alone, an average of 20% of professors at public universities have taken leave without pay to join the NGO sector or migrate to greener pastures abroad. At the University of Juba alone, 143 professors – or 24% of teaching staff – left over the last year. Things can only get worse.

To address this grave concern, the University of Juba has tried once again in this academic year (2018-19) to adjust the tuition fees in order to recover some value. Accordingly, medical students are being asked to pay SSP50,000 (about US$200), while engineering and social science students are required to pay average tuition fees of SSP32,000 (US$130).

As usual, the fee adjustment is being vehemently protested by the students. However, it is absolutely necessary to implement the new policy if the University of Juba is to remain open for delivery of quality education to its students.

Proposal for regional salary parity

Vice-chancellors of the five public universities, in cooperation with the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology, have made a proposal to raise the salaries of academics so that a full professor is raised from US$136 to the equivalent of US$3,500 per month.

This will bring monthly salaries at our public universities to the same level as Kenyan professors but slightly behind Uganda (US$5,000), Rwanda (US$4,900) and Tanzania (US$3,700). This pay adjustment will not only retain the current staff at our universities, but will be sufficiently competitive to attract academics from the region and further afield to come and work at our public universities.

If anyone is saying this is going to be too expensive for students and the government to afford, the alternative of having no competitive and well-funded higher education sector in our country is even worse and more costly.

We have one last chance to save the University of Juba and turn around our ailing higher education sector by acting promptly and acting positively.

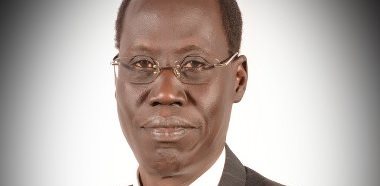

John Akec is the vice-chancellor of the University of Juba, South Sudan. The article was originally published by the University World News website.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made are the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.