The Dinka word Ngok, from which the people of Abyei derive their ethnic name, is a fish with three sharp fins described as ‘horns’. While its meat is delicious, it is not an easy fish to catch, as it threatens to dangerously pierce the fisher with its sharp horns. But this danger is purely defensive, never offensive.

And so it is with the Ngok Dinka. Like the other Dinka groups and indeed all the people of South Sudan, the Ngok are ferocious warriors. The nine chiefdoms of the Ngok Dinka used to ally themselves with two warring camps that fought devastating internal wars. The last internal war was fought in 1943 when Paramount Chief, Deng Majok, imposed severe prison sentences and heavy fines on those responsible for the outbreak of the fight, foremost from his own section of Abyor. The legacy of Deng Majok among the Ngok Dinka is now that of a peacemaker and a dispenser of justice without fear, prejudice, or favor.

The Ngok Dinka have remained courageous warriors who distinguished themselves in the two Sudanese civil wars (1955-72, 1983-2005) as exceptionally brave. The Ngok have however never been aggressors. They have always fought only in self-defense against external aggression. The wars of liberation in Southern Sudan in which the Ngok distinguished themselves were inherently in self-defense against racial, ethnic, cultural, and religious domination by the North. In the tribal wars with neighbors, those who died on both sides were within Ngok territory, never in the land of their adversaries. This fact, which applies to the recent hostilities, demonstrates beyond doubt that the Ngok fought only in self-defense against aggressors in their land.

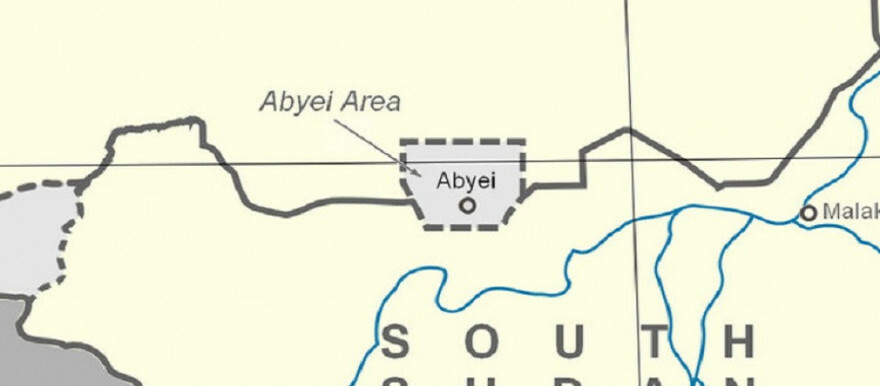

The Ngok Dinka are a relatively small group, but they have never hesitated in confronting existential threats against them. Faced by equally ferocious warrior tribes in their volatile region, often backed by the mightier power of the state, the overriding challenge for the Ngok Dinka is ‘to be or not to be’. Recent attacks by traditional aggressors from the North and now surprisingly by their kith and kin group from the South have brought the survival of the Ngok Dinka to a treacherous brink. There is a widely shared belief among the Ngok Dinka that these attacks from the north and south of the borders of the Abyei Area are coordinated by some misguided politicians and war merchants on both sides. The fact that some of the attackers killed in the violent clashes in the Abyei Area wore military uniforms of both armies reinforced this perception. If these allegations are true, they open a new page of conflict that the national leadership on both sides must take seriously and immediately address.

The Ngok Dinka are doing their best to protect themselves and have exceeded all expectations in fighting valorously in self-defense to repulse their aggressors with very limited capacity. Although they are effectively using their ‘three horns’ to fight aggression from multiple fronts, they are inherently at a severe disadvantage and need to be rescued from the threat of annihilation. In the interest of humanity, all those who are in a position to help are urged to undertake rescue operations with the sense of utmost urgency. The ‘three horns’ of the Ngok must now be redirected toward sharpened preventive diplomacy to mobilize humanitarian intercession and mediation. The three horns of the proposed diplomatic offensive must target South Sudan, Sudan, and the international community.

The two potential interveners with the ability to bring about immediate remedies are the two governments of Sudan and South Sudan, not only to stop aggression from their respective fronts but, even more importantly, to negotiate an end to the impasse over the unresolved status of Abyei. The people of Abyei have become virtually stateless, without the protection normally expected from the government for its citizens. There is no reason why a common win-win framework cannot be negotiated to the benefit of all concerned. In my extensive discussions with the national leaders of both sides and with international stakeholders over the years in my various national and international positions, this is a vision that appeals to all concerned. What is lacking is the will to act.

Who benefits from the internecine tribal violent conflicts that have engulfed the area, devastated the communities in the region, and poisoned bilateral relations between the two countries? The answer is unequivocally no one. In fact, everyone stands to gain from peace, security and stability in that it can contribute effectively to improved bilateral relations between the two nations, and thereby promote broader regional peace and security. Regional and international organizations, the African Union, the United Nations, and the Troika countries can undoubtedly help, but experience has shown that their authority is largely moral and persuasive and is therefore limited. They cannot impose a solution coercively.

The United Nations Interim Security Force in Abyei (UNISFA), while offering much-appreciated service, is by definition an interim arrangement, and does not have enough capacity to provide protection throughout the territory of the nine chiefdoms of the Ngok Dinka. Meanwhile, what the Ngok Dinka can do is continue to use their very limited capacity for self-defense to complement the efforts of UNISFA. No one can in good conscience tell them not to defend themselves in the absence of adequate national and international protection for their survival.

Meanwhile, all concerned, the governments of the two Sudans and their leaders, the Security Committees of the African Union and the United Nations, and the Troika countries, with the US as the UN penholder on Abyei, should take immediate steps to mediate an end to the impasse over the final status of Abyei. Former President Thabo Mbeki of South Africa and the African Union High Implementation Panel (AUHIP) which he chairs should be called upon to expedite their work and come forth with the long-awaited proposal for ending the impasse.

What is immediately needed is straightforward and easily doable: ending all violent activities; empowering the Ngok Dinka to manage their own affairs; ensuring the security of the area by the two governments with international guarantees; encouraging and supporting internally displaced populations to return to their areas of origin; providing the returnees with essential services to resume their normal life; generating self-reliant sustainable development through a strategy of self-enhancement from within by making effective use of their local material and human resources; and promoting peaceful existence and cooperation between and among all the communities in the border areas of Sudan and South Sudan. The immediate payment of the arrears of the two percent of the revenue accruing from the oil produced in the Abyei area which is allocated to the Ngok Dinka by the Abyei Protocol of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement would go a long way in covering the costs of the envisaged program. Lack of resources should therefore not be used as an excuse for inaction, especially given that these resources are the right of the Ngok Dinka.

Whatever the final status for the area the parties eventually agree upon, Abyei will remain a place that can either contribute positively to the cordial ties between and among the neighboring communities and their respective countries or be a point of confrontation and violent conflict, with negative ripple effects between the two countries and within the wider region. On a positive note, although Abyei is a small and relatively remote place, the eyes of the world are now focused on the area. It is inconceivable that the world can remain indifferent to the plight of the people in this regionally and internationally sensitive and strategically vital border region.

The desirable policy framework is obvious. What is needed is leadership and the will to act decisively. May enlightened self-interest and the wisdom of responsible sovereignty prevail with a sense of utmost urgency.

The author, Francis Mading Deng, is a politician, diplomat, and author.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.