In a legal battleground over democracy and rule of law, Section 60(4) of the South Sudan National Election Act 2012 (Amendment) 2023 faces scrutiny for what I describe as illegal, unconstitutional, undemocratic, and null and void. The controversy centers around the president-elect’s alleged authority to appoint members of parliament, a power not explicitly granted by the constitution.

The Constitution lacks any provision granting the president-elect the authority to appoint members of parliament for the people of South Sudan. Democracy hinges on the principle of voting, a fundamental right that citizens must exercise. The government’s defense, which relies on the practices of other countries in the region, merely involves copying laws without considering the unique constitutional context.

The president-elect is a representative of the people and a public servant, not the sovereign of the country. The true sovereigns are the people themselves, and citizens should have the autonomy to determine what is in their best interest.

Democracy serves as a crucial tool for fostering diversity and addressing systemic inequalities. Without proactive measures, certain groups may encounter barriers to advancement and equal treatment. Diverse representation in various sectors enhances decision-making, encourages innovation, and builds a more inclusive society.

Preferential treatment based on tribe, ethnicity, race, or gender is unjust to individuals who may be more qualified but are excluded from designated groups. Affirmative action can perpetuate stereotypes and stigmatize beneficiaries, leading to resentment and division.

Political equality, individual rights, and the rule of law empower citizens to hold leaders accountable, voice their concerns, and shape the trajectory of their society. Threats such as voter suppression, electoral fraud, and disinformation can compromise the integrity of elections and undermine public trust in democratic institutions.

Governments aim to address historical injustices and systemic inequalities by creating opportunities for marginalized groups, employing measures like quotas in education and employment, outreach programs, and targeted support for minority-owned businesses.

Ensuring every eligible citizen has the opportunity to vote without discrimination or undue influence requires provisions safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process, preventing fraud, and upholding fundamental rights to political participation.

In a democratic process, the president should not appoint minority group representatives in Parliament but rather allow them to participate through campaigning and contesting for the reserved 5% seats. Allowing the president-elect to appoint these representatives would be an abuse of the right.

Affirmative action initiatives can extend to political representation by encouraging diverse candidates to participate in electoral processes, such as through reserved seats or support for political campaigns led by individuals from marginalized communities. However, the government should only encourage candidates from minority groups to participate, avoiding undemocratic appointments by the president.

Election laws play a crucial role in promoting inclusivity in political participation. Addressing barriers like language accessibility, polling station locations, early voting options, and absentee balloting directly impacts marginalized communities’ ability to exercise their voting rights, contributing to a more representative democracy.

Pursuant to Article 8(1)(c) of The Treaty, South Sudan, as part of the East African Community, is obligated to abstain from measures jeopardizing the objectives or implementation of The Treaty.

The arguments made by South Sudan on the amended Section 60(4) of the Act, claiming it represents minority tribes, trade unions, and people with disabilities, cannot be verified in the plain text, as reproduced below.

Section 60 has been amended by altering subsections (2), (3), (4), and (5) of the Act, resulting in the following revised composition and election procedures for the National Legislature:

60. Composition of the National Legislature and Elections of its Members:

(2) (a) Fifty percent (50%) of National Legislative Assembly members will represent geographical constituencies in the Republic of South Sudan.

(b) Thirty-five percent (35%) of women members shall be elected through proportional representation at the national level from closed party lists.

(c) Fifteen percent (15%) of members shall be elected through proportional representation at the national level from closed party lists.

(3) There shall be five representatives from each State and two representatives from each Administrative Area in the Council of States, elected by members of the state legislative assembly and the Administrative legislative council, respectively.

(4) The elected President shall appoint five percent (5%) of the three hundred and thirty-two (332) members of the National Legislative Assembly.

(5) The total number of members of the National Legislative Assembly shall be three hundred and thirty-two (332).

The argument, however, confirms that the amended provision is ambiguous, overly broad, and restricts democracy. Notably, the plain text lacks any reference to “minority tribes.” Instead, it states, “the president shall appoint… 17 members of the legislature.” This provision contradicts democratic principles, fostering political discrimination and undermining good governance.

The impugned provision grants the president authority to interfere with the election of legislature members by handpicking 17 individuals of personal choice. This violates the democratic principles of a free and fair election.

It is excessively ambiguous, disproportionate, and grants the president unreasonable discretion to appoint and remove legislature members, effectively placing a section of the legislature under the President’s control. This provision restricts the right to vote and be voted into the parliament unreasonably and arbitrarily limits the election of legislature members.

The parliament cannot be considered separate from the executive when the president wields the power to appoint 5% of its members. This provision undermines the parliamentary role of overseeing and checking the executive, placing 17 members at the mercy of the president.

The mentioned provision violates Article 56. (1) (a) of the Transitional Constitution, which states that “Members of the National Legislative Assembly shall be elected through universal adult suffrage in free and fair elections and by secret ballot.” It also runs afoul of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance.

Furthermore, it is inconsistent with the Treaty and constitutes a breach of Articles 6(d), 7(2), and 8(1)(c) of the Treaty. The actions of the Respondent (South Sudan government) in this context infringe on the democratic rights protected under the Treaty.

Under the Treaty, the Respondent has an obligation to uphold the fundamental principle of the Community as outlined in Article 6(d) and 7(2) of the Treaty.

Article 23 of the Treaty tasks the court with ensuring adherence to the law in the interpretation and compliance with the Treaty. Additionally, Article 27(1) of the Treaty grants this court jurisdiction to interpret the Treaty’s provisions, making this application properly before the court.

Allowing the president-elect to choose representatives for minority groups, ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and trade unions undermines the participation of these groups in politics. Few fortunate individuals, whose capabilities and leadership skills were not tested, end up in leadership positions, denying their members the sovereign rights to participate in elections, vote, and be voted into government.

Section 60(4) of the Election Act contravenes Article 2, 3, and 56(1) regarding the sovereign authority of the people to decide who should represent them. The constitution did not delegate these rights to a third party; the Constitutional rights of individuals who are sovereign should not be decided by a third party.

All minority ethnic groups, people with disabilities, and trade unions emphasized in the government’s defense that citizens must have access to the ballots to decide and shape their future and destiny. The appointment process denies public participation and the obligation to be accountable for the views they should represent.

Appointees are compelled to pledge allegiance not to the state and the people they are meant to represent but to the president-elect, who dictates their positions. Correcting past wrongs is imperative as our country emerges from a dark history. We cannot revert to the shadows of history by having flawed election laws that grant the president-elect the power to appoint representatives for the sovereign people. This issue requires resolution by the empowered East African Court under Article 6(d), 7(2), 23, and 27 of the Treaty.

I contend that the violation of the rule of law and democracy is a matter for the Court to address whenever it arises. Any threat to democracy and the rule of law by a partner state violates the Treaty under Article 6(d), 7(2), and is deemed a breach of the Treaty.

Anything lacking legitimacy cannot be effective, and anything lacking effectiveness cannot develop legitimacy. Procedural impropriety constitutionally renders anything invalid as a tool of governance.

Anything done without the authority of the sovereign people under the Constitution of 2021, as amended, cannot be sanctioned by the Court as a legitimate governance tool.

While legislatures are meant to represent the people’s views in theory, in practice, they often fall short. The government’s actions restrict democracy and violate the rule of law under the guise of executing democracy, resembling more of a scam.

The significant mistake made by the entire National Parliament was passing laws without amending the Constitution. The Constitution should have taken precedence before enacting any subsidiary laws, ensuring alignment with constitutional principles.

Leaders derive their mandate to govern from the people through elections. The Constitution emphasizes “We the People,” signifying that power emanates from the people. Leaders should not obtain power from the President but from the constituencies they represent. This is why some of us oppose it. Every citizen is mandated under the constitution to defend it, and I am ready to meet government lawyers in court.

May God bless the Republic of South Sudan and South Sudanese families. Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

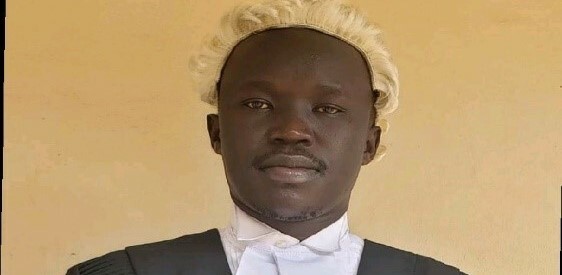

The author, Wani Santino Jada, is a South Sudanese advocate and a seasoned litigator at the East African Court of Justice (EACJ).

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and the responsibility for the veracity of any claims made rests with the author, not Radio Tamazuj.