It was distinguished Greek historian Herodotus who remarked during his overseas debut in the late 4th Century BC that Egypt was “a gift of the Nile”. His observation is no less true today than in the distant past as the Nile River remains Egypt’s sole source of life.

Imagine, the drop in the water level of the Aswan High Dam some years ago occasioned the low agricultural productivity and the severe downfall in industrial output in Egypt. The situation hastened the reduction in foreign exchange reserves and serious food shortages. Export earnings and government revenues also diminished substantially, leading to a decline in public services as well as essential development programs. Since the situation demanded increased imports for food, according to an Egyptian observer, Dr Elhan Afify, it resulted in an enlargement of deficit in the balance of payments, therefore, reducing the rate of savings and investments and consequently, lowering the rate of economic growth in Egypt. In addition, the fall of the water level of the Dam precipitated the low hydroelectric power supply, for the Aswan High Dam alone provides 22 percent of the national energy. Hence, it can be concluded that Herodotus was right when he regarded Egypt as a gift of the Nile.

However, as far as the Nile River is concerned, Egypt is in a very delicate position as the control of waters is in the hands of upper riparian states. For example, Ethiopia alone controls approximately 86 percent of all waters flowing to Egypt. The remaining 14 percent emanates from the White Nile River.

Given its volatile position, which, for half a century has been exacerbated by the political independence of southern riparian states, Egypt has been resolutely wielding enormous diplomatic deviousness and military threat to seek, impose, strengthen, and consolidate its hegemony over the Nile waters. Its course of action has persistently incubated the hydro-politics between downstream and upstream states. Reacting to this development, Dr Daniel Kende, an acute Ethiopian Professor of History recently wrote, “Since concern with the free flow of the Nile has always been a national security issue for Egypt, as far as the Nile goes, it has been held that Egypt must be in a position either to dominate the southern riparian states, or neutralize whatever unfriendly regimes might emerge there. It must have a hegemonic relationship with countries of the Nile Valley and Horn of Africa”. According to Professor Kende, when, for instance, upper riparian states are weak and internally divided, Egypt can rest. But, when they are prosperous and self-confident, Egypt becomes worrisome.

Such behavior has been repeatedly displayed by every government that comes to power in Cairo, especially top Egyptian political leaders. Chief among callous Egyptian politicians who strongly view the issue of the Nile waters as a matter of between life and death include the late President Anwar Sadat who once said, “Any action that would endanger the waters of the Nile will be faced with a firm reaction on the part of Egypt, even if that action should lead to war”. A similar military lyric was reverberated by the late President Hosni Mubarak at the Nile Basin Initiative after having taken with him the Minister of Defence to the conference. Mubarak warned the officials in attendance, “Anybody who wants to mess around with our share of Nile waters here is the Minister of Defence. We will take military action”.

With all these astonishing utterances directed towards southern riparian countries, it has become more clear that not until humanity ceases to exist, the rogue mentality will not be withheld by Egyptian policy designers and decision makers, because the arithmetic of the Nile waters on the side of Egypt has practically become a zero-sum game that she is determined to win. We have witnessed it enough from the way Egypt reacted to the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), and the uneven distribution of water percentages between her and the Republic of Sudan during the 1959 Agreement. Such a conflict and a deliberate onslaught of marginalization are no distance from the Republic of South Sudan so long as the White Nile River, which is about 5,584 km long passes through it. The serious warning about Egypt’s obsession with the Nile waters has been perfectly summed up by an anonymous political commentator who once pointed out, “Egypt is a country that has not abandoned its expansionist ambitions. It regards its southern neighbors as its sphere of influence. Its strategy is essentially negative: to prevent the emergence of any force that could challenge its hegemony, and thwart any economic development along the bank of the Nile that could either divert the flow of the water or decrease its volume.”

One important aspect of the White Nile controversy which is well worth knowing is that there is no unanimously agreed regime to regulate the utilization of water resources by riparian states, particularly between Egypt and South Sudan, between Sudan and South Sudan, and among these three riparian states respectively. The colonial and Egyptian-Sudanese attempts of 1891, 1906, 1929, and 1959, regarding the sharing of Nile waters between downstream and upstream countries were initiated primarily to promote and preserve both colonial interests and Egypt’s hegemony over the Nile. Interestingly, such instruments were negotiated and subsequently institutionalized a long time before the Republic of South Sudan seceded from Sudan in 2011. As such, her actions cannot legally be subjected to the terms and conditions of such arrangements.

Nevertheless, although there is no universally accepted mechanism to constrain the actions of all the riparian states, it is self-evident that any plan developed by a southern riparian country to utilize the White Nile water is always expected to face stiff opposition from Egypt, something it may even regard as an abomination or a ticking bomb that must be handled prudently. For centuries, the Arab Republic of Egypt has been the godfather and at the same time self-imposed mathematician of the Nile water resources, using her soft and hard powers to calculate water percentages required for every designated project in any southern riparian state.

Thus, the fundamental questions to ask in the absence of a cohesive water treaty are: how will the Republic of South Sudan handle the hydro-politics of the White Nile River? What will deter Egypt from subduing South Sudan when it begins to claim its sovereign rights over the White Nile water? How can South Sudan use its domestic and international leverages to claim its sovereign rights over the White Nile water? Will the current Egyptian diplomatic deviousness make South Sudan prosperous and peaceful? These questions, and many more, are so imperative in understanding Egypt-South Sudan relations concerning the White Nile River.

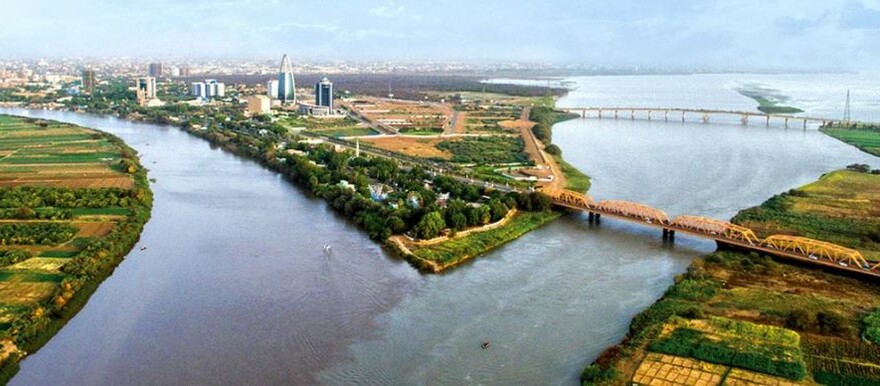

In this paradox, what must be conveyed is that the White Nile River is of great significance not only to the Arab Republic of Egypt but also to the Republic of South Sudan. It is, of course, a matter of national security concerns for both countries. For example, as Egypt’s economy is largely dependent on the Nile waters, so does the economy of South Sudan.

To underpin the substance of this debate, about two-thirds of South Sudan’s population is food insecure. While nearly 80 percent of South Sudanese living in urban centers such as Juba City largely depend on imported food and non-food items. Due to over-dependence on oil exports, the entire economy of the country is currently crumbling, leading to a substantial decrease in foreign exchange reserves and a deficit in the balance of payments, and consequently, aggravating inflation, and the high cost of living of South Sudanese ordinary citizens. In terms of national energy, it is believed that about 80 percent of the country’s power supply comes from imported generators. Also, too much reliance on these generators is causing both air and sound pollution in addition to the entrenchment of the country’s inability to embark on the industrialization program.

With all these long and debilitating accounts of our beloved country and its people, we strongly suggest an urgent need to utilize the White Nile water to aggressively confront the onslaughts of the ongoing economic slump, extreme poverty, over-dependency, and industrial backwardness. Although the incumbent political leadership of this country is still preoccupied with the implementation of the peace agreement, and it does not currently consider this issue a top priority that needs stout political action, we consider it a patriotic endeavor that must not be persistently ignored, especially at this precarious time. It is, therefore, our deeply held belief that the endless socio-economic interlocutors will soon stimulate South Sudan’s desire to exploit the White Nile water within its jurisdiction, where the hydro-politics shall only be moved in the spirit of a win-win solution.

About the authors: D. Garang is a South Sudanese fourth-year student of Environmental Science at the School of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, University of Juba. Currently, he teaches Geography at Venus Star High School. He can be reached via dgarangdengyoom@gmail.com.

Amaju Ubur Yalamoi Ayani is a South Sudanese Master’s student of Political Science at the School of Social and Economic Studies, University of Juba. He specializes in International Relations and Diplomacy and teaches Citizenship at Venus Star High School. He can be reached via amajuayani@gmail.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.