South Sudan’s first two years of independence was marred by disputes with Sudan over border demarcation and management of the oil sector that brought both countries to the brink of war. The oil shutdown following Sudan’s excessive fees demands for the use of its pipeline crippled South Sudan’s economy. Meanwhile, inter-ethnic violence caused hundreds of deaths in Jonglei, Lakes and Eastern Equatoria states. Shortly after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that ended the war in 2005, Garang died in a helicopter crash. His successor, Salva Kiir, pursued a more overtly separatist agenda.

The CPA formalized power sharing between the SPLM and the ruling political party in Khartoum, the National Congress Party (NCP), in 2005. The two parties held seats in a national unity government, and the South, ruled by the SPLM-dominated Government of Southern Sudan (GOSS) in Juba, was granted a large degree of autonomy which was marred by widespread impunity for human rights abuses and corruption in public institutions. While the aim of the CPA was to “make unity attractive,” but both sides failed to commit to it. The GOSS focused on a provision which allows the Southerners to hold a referendum on self-determination after six years.

The referendum was held in a peaceful and orderly fashion in January 2011. Almost 99 percent of those who participated cast their votes in favour of independence. Six months later, on July 9, 2011, South Sudan became the world’s newest nation. A separate referendum to decide the future status of Abyei, a contested area on the border with Sudan, did not take place as scheduled due to disagreement between South Sudan and Sudan on eligibility of those to vote.

That argument over who was eligible to vote led to increased tensions, which resulted in Sudanese forces occupying Abyei, causing approximately 10,000 people to flee. In June, both sides agreed to withdraw their forces to make way for a UN peacekeeping force.

South Sudan endured a rocky start as an independent nation, struggling to provide basic services, tackle corruption, and bridge ethnic divisions among its impoverished citizens. Internal insecurity was a serious problem. The SPLA faced a series of armed rebellions and inter-ethnic clashes, which killed nearly 2,400 people in the first half of 2011.

Relations with Sudan were hostile throughout 2012. Negotiations over the terms of South Sudan’s independence focused on issues including border demarcation, management of the oil sector, and the status of Southerners living in the North. In January, the government halted oil production, the source of 98 percent of its revenue, after Sudan demanded excessive fees for use of its pipeline. The decision catastrophically impacted South Sudan’s economy, forcing the government to adopt austerity measures and to freeze its development plans. On the part of democracy, the SPLM government in South Sudan has done nothing in providing good governance to the South Sudanese people as promised during the war of liberation. Several human rights activists lost their lives and the government due to its incapacity was silenced. In early 2013, the country was embroiled in a series of disagreements between the leaders of the SPLM on the way forward. It first started as a power struggle in the SPLM about who should be the leader of the Party in the run-up to the election in 2015, when the debate heated up, reconciliation became impossible which led to the subsequent dissolution of cabinet on 23 July 2013, suspension of SPLM secretary general with other members and the country became volatile to the voices of anti-violence, rule of law and order until the dark day in history of South Sudan (15th Dec, 2013).

Then from there, the country was marred by violence which includes extrajudicial killings with impunity, rapes, and displacements along tribal lines up to today.

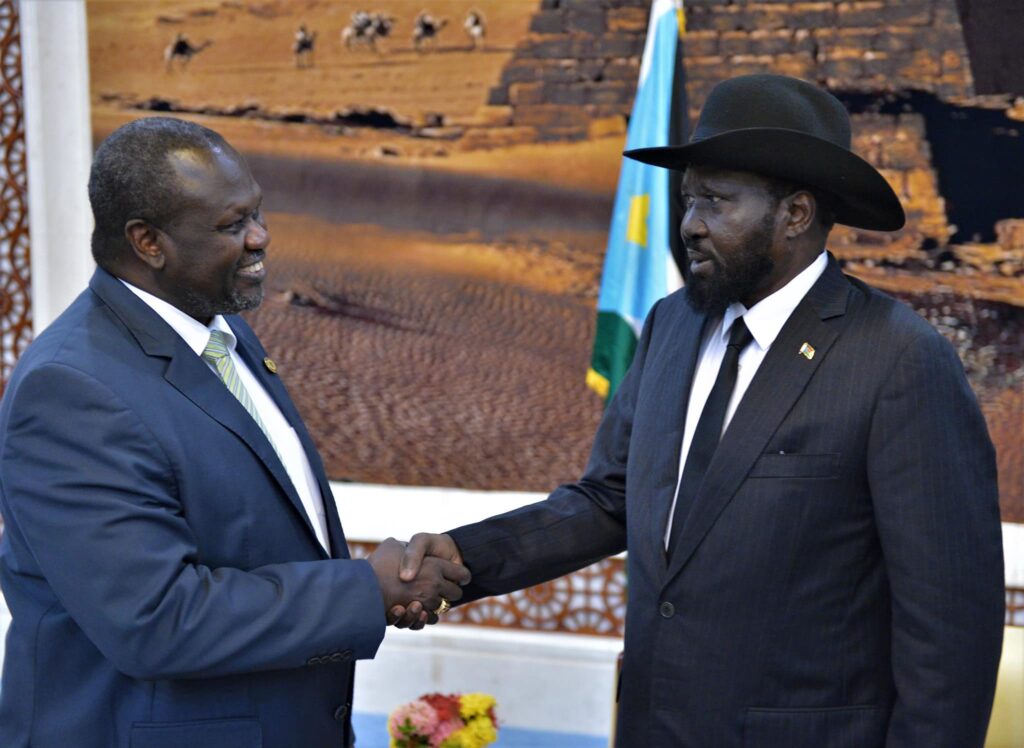

Given the history and the proportion of the effect of conflict on the citizens, one can concluded that Democracy in South Sudan is in its graveyard. The Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan of 2015 and the revitalized peace deal recently is more of dividing the cake between the elites/warring parties. It provides little on the trajectory the country should go through after the end of the transitional period which left many to wonder about the stability of the state in case there are disagreements about the results of the upcoming election as in the case in many African countries.

The author can be reached at markodak332@gmail.com

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made are the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.