By Duop Chak Wuol

South Sudan, the world’s youngest country, has faced near-constant instability since its independence in 2011, which has since escalated due to a devastating civil war in 2013 and a fragile peace agreement in 2018. Despite the efforts of multiple U.S. administrations, lasting peace remains elusive. This is primarily due to the actions of President Salva Kiir, who has deliberately undermined peace efforts and impeded political reforms to maintain his grip on power. While former Presidents Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and current President Donald Trump have had differing approaches to foreign policy, the key question becomes: With Dr. Riek Machar, the First Vice President of the young nation, placed under house arrest and the potential for a return to full-scale civil war, can Trump’s unorthodox, transactional foreign policy offer a viable path to resolving South Sudan’s crisis? This article argues that Trump’s unconventional methods might provide a unique breakthrough in South Sudan’s peace process, though these methods come with significant risks.

The Republic of South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on July 9, 2011, following decades of bloody civil war. However, an internal power struggle within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and ethnic tensions plunged the country into civil war in 2013, just twenty-nine months after its independence. The conflict, which lasted from December 15, 2013, to February 22, 2020, resulted in nearly 400,000 deaths, according to a 2018 report by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The number of people who lost their lives in the conflict is likely greater, as this estimate did not include conflict-related deaths between December 2018 and February 2020. The war forced millions of South Sudanese to seek refuge in the UN-run Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites across the country and in refugee camps in Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Sudan.

When the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) was finalized in September 2018, the South Sudanese believed that their suffering was ending and that a lasting peace was finally achievable. However, the citizens were totally unaware that President Salva Kiir was embarking on a deliberate plan to undermine and consistently compromise the peace process. Kiir publicly supported the full implementation of the R-ARCSS; however, behind closed doors, he sabotaged the peace process by covertly working to impede its execution. This tactic was designed to preserve the dictatorial political system that triggered the 2013 civil war. For example, instead of implementing the peace deal, President Kiir obstructed key peace bodies like the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC) and Joint Military Ceasefire Commission (JMCC) by denying them funding. His plan also included systematically weakening opposition parties by withholding the financial support the agreement mandates, which requires the Revitalized Transitional Government of National Unity to fund opposition parties based on their representation in the agreement. Kiir also consistently violated the peace implementation process by removing opposition figures from constitutional posts, even though the agreement states that he could only dismiss political and military representatives from the opposition with consensus.

These actions are among the reasons why the peace deal has remained largely unimplemented since September 2018. As of April 2025, the volatile situation remains unchanged. In the face of this perilous reality, the key peace figures, including Kiir and Machar, have decided to extend the transitional period in September 2024 and delay national elections until December 2026. Regrettably, it would appear by his actions that Kiir believes the specifics of the revitalized agreement are irrelevant. What matters to him is that the peace deal must be implemented solely on his terms, heedlessly ignoring the stipulations of the agreement. For example, on April 9, 2025, a small faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO) in Juba declared the replacement of Dr. Riek Machar with Stephen Par Kuol—a move orchestrated by President Kiir to further destabilize the peace implementation process. Stephen Par has now started urging Kiir to appoint him as the First Vice President, aligning perfectly with Kiir’s interests. This strategy mirrors the July 2016 SPLM-IO split led by Taban Deng Gai, which aimed at deepening divisions within the opposition and obstructing the peace process. This deliberate strategy breeds political misunderstandings between the parties, weakens governance, perpetuates ethnic hostilities, leaves national institutions underdeveloped, and exacerbates economic hardship. This is exactly what Kiir wants. He believes that if key aspects of the country, such as a permanent constitution or political reforms, remain weak, he can continue ruling as he pleases. This political turmoil also raises questions about whether it is feasible for Kiir and Machar, who have implemented less than thirty percent of the agreement over the past six years, to complete the remaining seventy percent within the next twenty months.

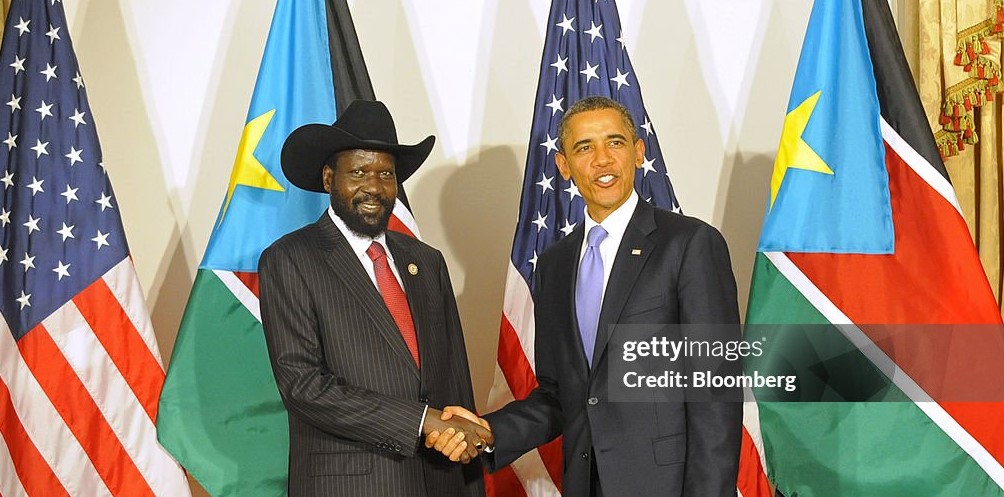

It is worth noting that U.S. foreign policy rarely changes, regardless of which party controls the presidency. However, presidents have different interests they wish to pursue for their own legacies. Until recently, the United States had been, at the very least, the midwife—if not the parent—of South Sudan. The hard work of American diplomacy—first during the presidency of George W. Bush, followed by strong lobbying from the American evangelical community and later the administration of Obama—was instrumental in South Sudan’s 2011 referendum, its peaceful secession from Sudan, and recognition as the world’s newest independent state. Obama, Biden, and Trump’s past policies were similar, with one significant difference: Trump imposed an arms embargo that Obama had refused to impose for more than three years.

Former President Obama’s foreign policy on South Sudan, though vocal in its condemnation, failed to take meaningful action to address the crisis. Soon after the civil war broke out in Juba on December 15, 2013, the Obama administration appeared to have been caught off guard. For example, when the United States consulted East African leaders—especially Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni—as to the appropriate strategy that could be crafted and designed to contain the situation, Kampala simply told Washington it was ready to deploy troops to Juba. Museveni asserted that Ugandan soldiers would be in Juba to protect vital government and public institutions until the situation returned to normalcy. Obama agreed, and the U.S. helped finance the initial deployment of Ugandan troops to South Sudan, with the understanding that Uganda was acting in good faith. Unfortunately, the Obama administration had been deceived by President Museveni, who was not committed to the establishment of stability on the ground in South Sudan, but rather had only months before struck a deal with President Salva Kiir, well before the civil war had erupted. Museveni was merely sending Ugandan troops to South Sudan to protect his East African regional ally, Kiir. Ugandan soldiers were also publicly fighting alongside South Sudan’s soldiers against the South Sudanese rebels. Obama then shifted his policy to a strategy of containment, focusing on peacekeeping initiatives, humanitarian aid, and diplomatic pressure.

Tragically, Obama’s foreign policy on South Sudan was an utter failure. A few weeks before his presidency ended, Obama declared at a news conference in Washington, DC, “I feel responsible for murder and slaughter that’s taken place in South Sudan that’s not being reported on, partly because there’s not as much social media being generated from there.” Obama’s statement was not only a grave mischaracterization of the situation quickly evolving in South Sudan, but it also conveyed a deeply serious misjudgment on the part of the President. In that press conference, what President Obama could have more clearly and candidly communicated to the American public and the international community was that it was his former National Security Adviser, Susan Rice—rather than social media—who played a central role in shaping the narrative surrounding the situation in South Sudan. I do not know if the Obama administration engaged in selective morality at the time, but the actions of his national security advisor suggested otherwise. It has been, and remains, widely known in South Sudan that Rice acted in ways suggesting alignment with the interests of Presidents Kiir and Museveni. Rice’s questionable position on South Sudan’s civil war was well-documented. Consider the following conclusions unflinchingly drawn by Foreign Policy magazine in January 2015: “…But, Rice, the former U.S. national security advisor and a long-standing champion of South Sudan, has for months resisted appeals from key allies, including Britain and France, and members of Obama’s national security team…to push for the weapons ban, according to more than one dozen foreign diplomats, human rights advocates, and congressional officials interviewed by Foreign Policy.” As demonstrated by Foreign Policy’s investigation, one wonders why former President Obama accused social media of willfully neglecting to report about South Sudan’s atrocities when, in fact, it was clear to all involved that the opposite was true.

U.S. foreign policy under former President Biden, who served as vice president under Obama for eight years, was similar to Obama’s, focusing heavily on multilateral diplomacy, the United Nations, and selective engagement with regional actors, such as East Africa’s regional bloc, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). Biden did not reverse Trump’s policies toward South Sudan; his approach primarily centered on humanitarian assistance and pressuring Kiir and Machar through multilateral diplomacy to achieve lasting peace.

In contrast, President Trump’s foreign policy has been less focused on traditional diplomatic efforts; rather, his approach appears to be more direct and unilateral when compared to previous administrations, including Obama’s. In his first term, Trump’s policies—most notably the unprecedented arms embargo on South Sudan and the suspension of direct financial aid to its government—stood out as a bold and strategic response to a deepening crisis. His “America First” stance and skepticism toward multilateral institutions presented a unique opportunity for peace in South Sudan by disrupting conventional diplomatic channels and possibly engaging controversial actors who had been previously excluded from negotiations. However, this unorthodox approach carries some risks, such as exacerbating tensions or undermining long-term stability. This could involve navigating the complex East African regional political dynamics, potentially alienating Kiir’s main regional ally, Museveni, who is complicit in South Sudan’s political crisis, or may undermine the implementation of the peace agreement. The success of such a strategy would depend on balancing these challenges while leveraging his unpredictability to shift—or perhaps, change the dynamics of the tenuous peace process.

In light of the ongoing conflict in South Sudan, it is crucial to explore effective strategies that can encourage peace and stability. A crucial strategy would involve imposing punitive sanctions on the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) and blacklisting South Sudan’s oil sector as strategic measures to address the conflict. It is important to note that the Ugandan military has been complicit in supporting Kiir’s brutal campaign against civilians and armed groups that oppose his policies, further fueling instability; thus, targeting the oil sector would disrupt a key financial resource, driving the conflict. These sanctions would exert economic pressure on both the Ugandan and South Sudanese governments, encouraging them to engage in genuine peace talks. Such actions could undermine violence-driven networks and ultimately encourage a shift toward peaceful negotiations between Kiir and Machar.

While the diplomatic failures of past U.S. administrations, particularly under Obama, demonstrated the limitations of traditional peace efforts in South Sudan, Machar’s house arrest not only isolates him from the political process but also prevents the opposition from having a full seat at the negotiation table, leaving the peace process vulnerable to manipulation by President Kiir. This, in turn, reinforces the deep political divide and undermines the prospects for lasting stability in the country. Trump’s unorthodox foreign policy approach presents a potentially transformative, but uncertain alternative. His willingness to bypass multilateral institutions, impose direct sanctions like the arms embargo, and engage with controversial actors could disrupt the entrenched dynamics that have long hindered progress. Ultimately, Trump’s transactional style might offer a unique opportunity to break the deadlock in South Sudan. Still, its success hinges on carefully navigating these risks to shift the peace process in a meaningful and sustainable way. To bring genuine peace to the young nation, given the complexity of East African regional politics and the fragility of South Sudan, Trump should strengthen U.S. relations with other East African leaders rather than relying solely on Museveni. He should also implement humanitarian programs for South Sudanese refugees in neighboring countries, as well as for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) within South Sudan. For too long, U.S. foreign policy toward South Sudan has been reactive, tethered to outdated alliances and cautious optimism. If Trump’s approach—flawed as it may be—proves anything, it is that disruption can be a tool when traditional diplomacy has exhausted its influence. These initiatives could serve as a strategic policy alternative to blacklisting the country’s oil sector by the United States, as it could result in negative consequences for them. This is the right time for the United States of America, under President Donald Trump, to help bring about lasting peace and write a golden chapter for the suffering people of South Sudan.

The author, Duop Chak Wuol, is a political analyst, writer, and former editor-in-chief of the South Sudan News Agency. A graduate of the University of Colorado, he specializes in East African security and geopolitics. He can be reached at duop282@gmail.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.