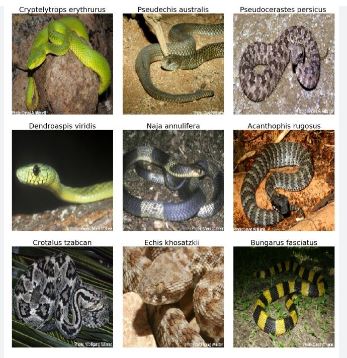

Médecins Sans Frontières, also known as Doctors Without Borders, teams in South Sudan have embraced AI technology to identify snakes, to improve snakebite response. The innovative initiative aims to develop a robust snake identification database using a collection of over 380,000 snake images.

This software, crafted to assist medical staff in real-time, focuses on distinguishing between venomous and harmless snake species, recommending appropriate actions to treat patients.

Snakebite envenoming is a significant health challenge globally, particularly affecting remote and underserved communities. Between January and the end of July 2024, more than 300 patients had been treated in MSF medical facilities across South Sudan.

“I remember a time when we used photo albums to identify snakes in MSF hospitals. Medical staff would flip through pictures to figure out which snake had bitten a patient,” said Dr. Gabriel Alcoba, MSF Medical Advisor for Snakebite and Neglected Tropical Diseases at MSF. “I witnessed this firsthand in South Sudan and other countries while working on snakebite envenoming and other neglected tropical diseases.”

He added: “Today, experts have created a snake identification database with 380,000 photos of snakes from different countries, using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.”

According to Dr. Alcoba, this innovative approach is now being piloted around two MSF hospitals in Twic and Abyei towns in South Sudan.

Together with the University of Geneva’s One Health Unit and support from MSF teams on the ground in South Sudan, as well as the medical and innovation departments at MSF in Switzerland, MSF is improving its database.

“We are developing software that uses AI to help identify snake species in the field, distinguishing between venomous and harmless snakes. This software can recommend the best action for a person bitten by a snake before they reach a hospital,” Dr. Alcoba. “We are currently working on collecting quality photographs to feed into this software. South Sudan has one of the lowest numbers of snake ecological studies but also experiences high rates of snakebite admissions in MSF hospitals, especially from May to October.”

He explained that for the AI to identify a particular snake, they need a photo of it, either while it is still alive (while taking all necessary precautions) or, when the snake is dead, (still taking great care since it could still bite).

“If someone has been bitten, the bite victim or someone nearby can try to take a photo of the snake after the bite occurs, but this must be done with extreme caution. If it was not possible to take a photo at the time of the bite, our staff can go back to the bite site and try to take a photo of the snake, again with great care,” he stated. “Once we have a photo, it goes into the AI software, which compares it with thousands of images to identify the snake or add it as a new entry with GPS coordinates.”

According to the medic, early results are promising; the AI sometimes identifies snakes even better than experts! For instance, it can differentiate between venomous snakes like the Egyptian Cobra or Black Mamba and harmless ones like the African House Snake.

“With better-quality photos, funding, and more research, this snake-AI app could provide real-time help for patients, from snake identification to choosing the right antivenom,” he said. “More research is still needed. Often, patients receive the wrong treatment because the snake isn’t correctly identified, or valuable antivenom is wasted on bites from non-venomous snakes, which can also cause serious side effects. Antivenom is rare and extremely expensive, costing a patient anywhere from a month to a year’s salary.”

Snakebite envenoming is a global health concern, associated with population displacement and climate shocks such as floods. Every year, five million people are bitten by snakes; of those, two million suffer severe effects, and between 81,000 and 138,000 die as a result of snakebite envenoming, according to WHO data.

Snake venom can cause three major syndromes: skin swelling, muscle destruction, and fatal hemorrhages or respiratory paralysis. Snakebite envenoming is classified as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD), mainly affecting people in remote, rural, flooded, or conflict areas in low-and middle-income countries. Consequently, it is not a lucrative market for big pharmaceutical companies or policymakers, despite the millions affected. Indeed, research on effective, “polyvalent,” less complex, safer, and affordable antivenoms has not been prioritized.