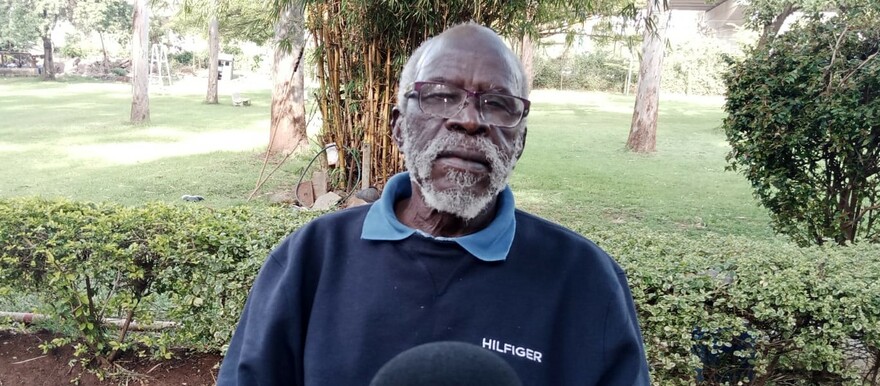

Prof. Taban Lo Liong is a South Sudanese academic, poet, and renowned writer of literary criticism and fiction.

He currently teaches at the University of Juba. Radio Tamazuj recently caught up with him in Nairobi, Kenya where he launched his book ‘After Troy’. He spoke about his childhood, his pursuit of education, and the quality of University of Juba graduates among other things.

Below are edited excerpts:

Question: Who is Professor Taban?

A: My name is Taban Lo Liyong. I am a Kajokeji boy who grew up in Uganda, worked across east Africa, and went to study somewhere else, and now I am here. I came to Nairobi for health reasons and lately my health is improving.

I was born in 1936 in Kajo Keji, about 100 miles south of Juba. When I was young, an aunt wanted me dead so my parents were urged to go away to Uganda so that I would not be killed because that woman came with poisoned roasted cassava and wanted to kill me using that. So, I was taken into exile because that was the only way I could be saved from the woman. This happened around 1939 or 1940.

Q: Why did she want to kill you?

A: She had killed two of my father’s elder wives by poisoning. She did not want my father who was very active and collaborative to make more developments in the police service of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan than her husband. So, it was a matter of competition in the family because my father was progressive and getting promoted and her husband was not.

Q: Talk to us about how you came to love teaching and your education journey.

In Uganda in 1945, there was a pandemic and everyone was asked to go and be inoculated and I went. At the same time, the headmaster of the local school asked the chief to help enroll pupils in the school. So I and other children started school in May 1945. That is how I went to school. Most of the South Sudanese in Uganda used to work in the (cotton) ginnery and not go to school. In our area in Bobi, in Acholi District, I was the only person who went to school.

I went far as education is concerned; in primary school, I completed primary 1 B, 1 A, and three, and in secondary, I went to junior one, two, and three, and then I went to senior one, two, and three.

The number of schools I completed in Uganda was three and then I went to a teacher training college in Kyambogo in Kampala. I trained as a teacher and when I came back to Gulu and became a teacher.

Later on, I got a scholarship and went to America, not as a South Sudanese, but at that time, I was taken as a Ugandan. Uganda was about to get independence and Americans wanted friends from Uganda so there were scholarships for those who did well so that is how I went to America in 1952.

When I went to America, I joined Howard University in Washington D.C. where the current American vice president also studies, and got a bachelor’s degree in literature and journalism afterward I did a master’s degree in literature in Iowa.

Question: Why did you focus on Literature, specifically on African culture?

My decisions have always been made after a tragedy has struck. During my first year in America, I fell sick and after four days of being bedridden, a telegram came to say my father had died in Bobi in Uganda. I felt I had lost something very important and my mother and my sisters back in Uganda were worried about how I would receive the news.

Later on, I decided to study and learn the English language to mourn my father because he did everything for me, including leaving the police service of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan to take me to Uganda to save my life. He died after paying the dowry for my first wife. So, I asked myself why God took away my father who was very progressive before he could enjoy anything from me apart from a bicycle I had bought him from my salary as a teacher.

So, I studied English literature to be able to mourn the fate of Africa in honor of my father. So, all deaths were like my father’s death.

Q: How many books have you published so far?

A: I do not know but between 15 and 20.

Q: What did you do after your studies in America?

A: When I was completing my studies in America, I had written articles and so when I was returning home, my name had come ahead. I was coming back to apply to go and Work at Makerere University in Uganda but there was an Englishman who was a homosexual. I do not know how he perceived me, but we did not get along very well when I was doing the interview.

So, after that, I went to Nairobi for a conference but I had sent a manuscript titled ‘The Last Word’ for publication. After they read it, they told me that they were looking for someone to work at the Center for African Studies in Nairobi and asked me to apply. So, I was recruited because of the book. That is how I got into Nairobi University.

Also, when I applied, I wrote that when I was studying for my master’s degree, with honors in creative writing in Iowa, I made a sculpture of a pot that could accommodate four people. So, the fellow said if I had made such a sculpture, then Nairobi University needed me. So, In 1958 I was appointed for making a pot.

Q: After Nairobi University, you taught in many places including Japan and South Africa. Where are your fondest memories?

A: I worked at Nairobi University for seven years and my best young days were spent teaching young people of Kenyans like Awuor Anyumba and most of them have already retired from Nairobi University. They also thought that I had already retired but I am still working at Juba University.

Q: What is the secret to your longevity in academia?

A: A chief told my father, actually ordered him, to go and buy me a school uniform so that I could start school the next Monday. My father agreed and so I knew that I had been ordered to leave village life and go into the new world. I started going to school and doing very well because I had been ordered by the chief. Therefore, who am I to leave school when my chief ordered me to go to school? That is why I am still here from 1945 up to now I have never left school. Sometimes I am teaching and at times I am writing.

So, I have asked my maker to keep me alive for as long as I am active and can do something.

Q: What is your take on the reading culture in South Sudan and Africa?

A: Some of our people have a belligerent culture and even fight their uncles and brothers. What can stop such a person from fighting you who is an ordinary person who is not known to him? So, if people cannot accept their uncles, how do you expect them to welcome a white man for example? So, anything an outsider brought, that we did not like, we did not take and that is where the problem is. If the culture of the Nilotic was different, things would be different, but again the Shilluk progressed. So, the question is what happened to the Shilluk that did not happen to their neighbors? The culture which the Anglo-Egyptians and white men brought was distributed to the other regions and we never became Muslims.

Q: Do you think education can change the never cultures in South Sudan?

A: For my book launch, we had expected the Dinka society in Nairobi to come and perform their cultural dance. A South Sudanese community was coming to participate in something another South Sudanese was doing. I was going to ululate but unfortunately, they did not come. One person came and read a poem. So, slowly by slowly, they are coming out of that culture and therefore we have to give them time. The educated ones should work hard to bring up their fellow relatives to say in the new country called South Sudan, at least we are also progressing, not by cheating but by following the new culture of education and I am looking forward to it.

I get angry when I am teaching and my students cannot understand English. I am one of the best speakers and writers of English and now in my home people think it is not important to know English.

I am begging my fellow South Sudanese Dinka and Nuer to send their children to school. The battle for the development of South Sudan is difficult if it is left on the shoulders of a few people only so everybody should help.

Q: Children are in refugee camps and IDP camps in the country and missing out on education. What would you like to say to the leaders about this?

A: I would like to tell my brothers, Salva Kiir, Riek Machar, and others, including (Rebecca) Nyandeng; please you are educated and you know the value of education. So, please welcome this thing called education, this thing called progress, so that it can reach every part of South Sudan.