BY LAWRENCE MODI TOMBE

My childhood years, like my contemporaries, were trapped in the Sudanese political upheavals of the 1950s through to the first north-south civil war years that ended in 1972. Those childhood experiences greatly influenced our perspectives about post-independence Sudan.

To that end, my journey through the Sudanese political storm of the 1950s started in 1953 when my father left government service for politics. Like my colleagues (Charles Bakhiet, Stans Awad, John Jumi, Mark Loro, Marcello Rondyang), I was schooling at Kator Elementary School back then. As Charles mentioned, all schools in Juba Municipality and across Southern Sudan were closed in prelude to the 1955 revolt that we knew little about back then.

The military insurgence, dubbed the ‘Torit Disturbances’, was the start of the first civil war in South Sudan. In those early childhood years, I had a bury understanding of the causes of that armed uprising. I gradually grew up into knowing its seriousness much later in life. Earlier than that, my generation was rudely introduced into causes of that serious armed uprising as we grew up. The conflict, as we know, was rooted in total dominance of politics/governance in Sudan by the Northern rulers, right from the start of the self-rule period in 1953 through to the independence years up to 2004.

One of the key triggers of the Torit rebellion, as we know it, was Ismail Al-Azhari’s incitement of Northern Sudanese senior government officials in the South to execute ruthless measures against Southern political leaders and informed citizens measures aimed at suppression of the federation call in the South at the time. Stories circulating in South Sudan back then claimed that Azhari’s message was received in the Juba Telegram Office in a coded form. Although the wire message was labeled top secret, it was stolen from the postmaster’s drawer, sneaked out, and deciphered by Reuben Yacobo (a Southern clerk at the post office) and translated into English by Fraser Ako – a civil servant working at the Province Headquarters (Mudoria). During those childhood years, I knew Fraser Ako very well as a football star in his JTC (Juba Training Centre) upskilling years.

Fraser handed the decoded content to the ‘Juba Secret Committee’ run by the veteran politicians Daniel Jumi and Marko Rume. Whether Azhari’s message was forged as claimed by the Northern rulers in Khartoum or not, the telegram was extensively politicized in the South a well-circulated document that aggravated the north-south tensions, which in turn contributed to the outbreak of the revolt in Torit on August 18, 1955. In those early childhood years, my generation could not understand the politics around the telegram, although flashes of Azhari’s saber-rattling message kept knocking in our young brains. I remember those disturbing news flashes very well and was aware of the instability about to engulf Southern Sudan at that stage.

Juba town was deserted following the outbreak of the military rebellion in Torit on August 18, 1955. At the escalation of the fighting and the resulting insecurity, the town dwellers were forced to flee to their respective villages for refuge. Our family fled to Gondokoro (my maternal uncle’s village) for safety. Our escape to the countryside took place in the absence of my father who was embroiled in political conflict.

We stayed away at Ilibari (Kondokoro) in the height of the military uprising; and only returned to Juba in October 1955 after the state of normalcy was reinstated in the city.

Our coming back to Juba town was followed by the birth of my brother, the Late Wani Tombe, in November 1955. Although Wani Tome’s arrival in our midst was a welcomed and exciting event in those difficult times, the family hardly settled down to normal life due to the insecurity that prevailed in Southern Sudan. However, a state of normalcy returned to Juba town in the first quarter of 1956.

A worrying and sad development occurred when the citizens in Juba started to witness convoys of trucks arriving town after the 1955 Torit army rebellion – military lorries carrying ex-soldiers involved in the rebellion brought in captivity for military trials. The transportation of the captured soldiers, driven from Eastern Equatoria to Juba, were a daily occurrence that lasted up to the second quarter of 1956. The arrival of our imprisoned heroes drew large crowds to the Juba Ferry-Malakia Road to witness the heart-aching spectacle. It was a painful experience implanted in my mind to date.

Incarcerated in Juba Prison, the ex-fighters underwent military tribunals set up in the Juba Town Council Hall – an assembly chamber turned into the Jubek State Parliament in the post-CPA years. The entire high-walled prison and the surrounding administrative premises of the Juba District Headquarters were cordoned off with barbwires for imprisonment of the ex-soldiers. Heavily armed Northern soldiers guarded the fenced-off area during the trumped-up military trials. Anyone within the vicinity during the court-martials watched platoons over platoons of hero fighters – dressed up in the beautiful No. 2 Battalion fatigues -marched from the prison to the Town Hall for the show military tribunals. Gripped by a child’s curiosity, I along other children went on several occasions to witness for ourselves the marching away of the incarcerated ex-soldiers to the military courts and back to prison after the summary trials. One cannot forget those sad and painful events!

The ex-fighters condemned to death were summarily executed by firing squad at the foot of the Körök Mountain (‘Jebel Kujur’) on the Juba-Yei Road. I gathered in later years that over 300 soldiers including the leader of the Torit military uprising, Lt. Rinaldo Loyelo, was among the rebel soldiers murdered at the foot of the mountain. On those heart-breaking killings, the citizens in Juba Town painfully heard echoes of gun firing on daily basis in the wake of those executions, as our national heroes fell, paying the ultimate price for freedom of Southern Sudan. Many citizens in the city wept openly over those sad endings of our heroes. In those tender years, I found myself rapped up in the tempo and pains of the liberation struggle, which my generation brutally endured down the war years. At that early stage of my growth, I wondered why our freedom fighters surrendered so easily to the enemy, only to end up in death rows the way they did. Back then, I understood nothing of the complexities that surrounded that total capitulation of our freedom fighters to the enemy. Equally disillusioned about the total surrender of the Southern troops, the people of Southern Sudan back then wondered why their heroes easily laid down their arms in that manner without putting up a fight against the Sudan government forces. Many factors contributed to those fatal hesitations. Answers to those queries are lodged in the total trust Southerners had in the colonial administration. To that end, the people of Southern Sudan entertained the idea that Britain, a Christian nation, was in support of the Christian cause in Southern Sudan, which was a huge error that continues to haunt us to the present times.

That naive and casual outlook in our relationship with Britain was the Achilles heel in our liberation struggle in the following years. Sir Alexander Knox Helm, the last British colonial Governor General in Sudan (1954-1955), exploited that blind trust by convincing Rinaldo and the rest of the No. 2 Company troops to capitulate. Loyelo accepted that fatal enticement by handing himself into the Northern troops in Torit. Sir Knox Helm earned that surrender of a dedicated freedom fighter by telling him that Prime Minister Ismail Al-Azhari had promised to accord him (Rinaldo Loyelo) and his soldiers a full and fair investigation leading to their pardon if they surrendered unconditionally. Sir Knox gave his assurances to that false Azhari’s testimony. The outgoing colonial masters and the new rulers of Sudan worked together for laying the basis for Northern dominance of politics and power in post-independent Sudan.

Not bothered about the serious implications of the Governor General’s telegram, Rinaldo handed himself in and signed the surrender terms on August 28, 1955. Most of the rebel soldiers surrendered amass. Of the 1,770-strong No. 2 Company soldiers jailed on those fatal surrender terms; majority of them were lined up straight away for the court martial trails conducted in Juba. Rinaldo Loyelo along the other liberation soldiers were sent to the death row on those empty promises and accounts.

Sadly, an article or clauses for exoneration of the rebels were glaringly absent in the telegram. Cdr Loyelo and all the No 2 Company Battalion fighters were not pardoned after those false assurances by Sir Knox Helm. All of them were either sentenced to death or brutally punished with liquidation of the Southern army command thereafter. For the ex-soldiers sentenced to prison, they were sent to the notorious Suakin Prison in Northern Sudan to serve long jail sentences with hard labor ranging from 10 to 30 years. The majority of the imprisoned ex-fighters died in captivity due to brutal treatment, harshness of prison life and the extreme weather conditions in Northern Sudan. Many of our political leaders were incarcerated including Clement Mboro who was jailed in Juba Prison from 1960 to 1962.

The people of South Sudan paid dearly for the false hopes in our so-called external friends, who prepared the Northerners to rule the Sudan without participation of Southerners. The sum total of those calculated schemes against the South was the reason why Southern Sudanese opted for the armed struggle for charting their political future. The unfounded trust in ‘our British friends’ were costly errors that resulted in massive human loss, which set back the clock of the liberation struggle in Southern Sudan at the time. The first-civil-war experiences that I underwent in those early childhood years were hard reminders of the life awaiting us children of Southern Sudan, as we grew up in that insecure environment. The extreme power exclusion that Southerners witnessed from the late 1940s through to the self-rule period were political developments that generated the 17-year civil war, which raged from 1955 to 1972.

I salute all the 1955 army-rebellion heroes for paying the ultimate price for our freedom; and for setting up the nation-state agenda yet to be reached. Their revolutionary legacy will remain with us forever.

This article is an extract from Lawrence Tombe’s autobiography, ‘My Life Story’-a memoir.

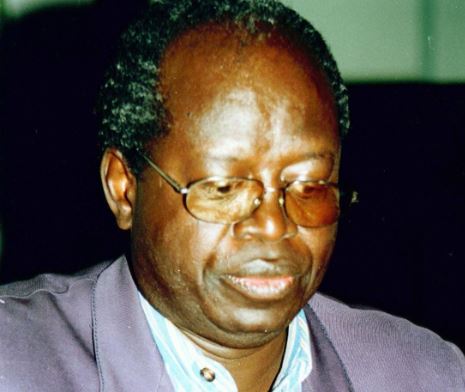

The author was born in Juba and attended early education in South Sudan in the 1950s and early 1960s and thereafter continued his education in Uganda graduating from Makerere University with a B.Ed. (Honours) degree in 1972. On return to Sudan in 1973, he was engaged in the Sudanese public service in various capacities from 1973 up to 1993.

He served as a cabinet minister, a parliamentarian, and a top civil servant, experiencing public sector governance from the three perspectives. Tombe left the diplomatic service in 1993 after serving in Romania as Sudanese ambassador for four years. He successfully sought asylum in the UK, having exposed to the world human rights violations of the Omer Bashir military regime.

At ratification of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, Mr. Tombe participated in the rebuilding process of the new country at the private sector level; he later served as a governance consultant in the government of South Sudan for one and a half years, 2014 to mid-2015.

He, along with others, founded Skills for South Sudan (SKILLS) in 1994.