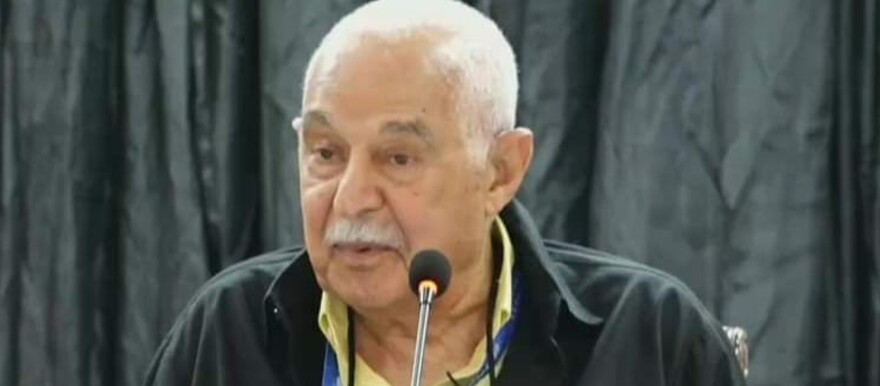

Tag Elkhazin is an Adjunct Professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, and has 50 years of experience, expertise, and engagement with the Nile waters. Lately, he has been engaged in several initiatives with the Netherlands and the Government of South Sudan.

In an exclusive interview with Radio Tamazuj, Prof. Elkhazin described the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by the Egyptian Government and the Government of South Sudan as ugly and a sellout to the Egyptians for about USD 24 million.

Below are edited accepts:

Q: Prof. Tag, there has been a lot of confusion in South Sudan lately, especially regarding the River Nile and its tributaries. As an expert, could you explain to our audience what is happening?

A: Very quickly, let me tell you a little bit about the Nile itself. In South Sudan, when we are talking about the Nile, we should be talking only about the White Nile because we have nothing to do with the Blue Nile. The Blue Nile originates in Ethiopia in Lake Tana, and it comes down to Bahir Dar and then into the Blue Nile. It produces about 86 percent of the total discharge of the Nile waters. So, the entire White Nile is producing only about 14 percent but it is a steady 14 percent. So, that is the situation with the Nile.

We do not have a cooperative framework agreement that regulates the White Nile or the entire Nile although it is the longest river in the world. The cooperative framework agreement is waiting for Article 14B. And there are two versions of that. The version of the Egyptians and the Sudan will leave no water for anybody else while the version of the Great Lakes countries will leave water for everybody. So, we need to read well the 1929 agreement between Egypt and Great Britain and the 1959 agreement between Sudan and Egypt, and we need to be mindful of the Sudd, which is the largest wetland in Africa and the second largest in the world after the Amazon.

Regarding the geopolitics, there are what we call water policies and water politics. Water policies are how you manage the water. Water politics is bringing pressure to bear on the different parties so that one gains more than the other. This is what Egypt and Sudan are doing, and South Sudan needs to develop capacity so that they are up to that. So, what is hurting us now in South Sudan is the water politics because the water policy is normally dependent on the 2 sciences of water, which are hydrology and hydraulics. Hydrology is the quantity of water, and hydraulics is the energy in the water that generates electricity.

Q: Prof. Last year, there were heated discussions on the issue of dredging or clearing of the Nile and its tributaries. Can you tell us the difference between dredging and clearing of the Nile?

A: Dredging is when you tamper with the profile, the basics, and the courses of the river. So, when you deepen the river, when you widen the river you drain more water from the source, and you drain more water from the natural running water. And that is very dangerous because you are going into the unknown.

You never know what is going to happen to the river or all the life in the river. If you take Bahr Naam, 11 different types of fish live there. The evaporation from the Sudd is what gives us the rain in Western Equatoria and northern Uganda.

So, dredging is when you tamper with the profile and the content of the river. The clearing is when you have got obstacles that you clear, a barge that sunk, aquatic weeds that have infested the area, and filth that has piled up in one area or the other. So, you clear the debris, you clear what is not natural in the river.

Cleaning is generally on the surface. The River Transport Corporation started in 1912. The first barge from Kosti to Malakal sailed in 1913. Every year for 100 years, until 2011, the River Transport Corporation was cleaning the part of the White Nile and they even diverted to Shambe and cleaned there, and the depths of all the vessels were only 4 feet, 120 centimeters.

That is all you need to have the natural flow of the river. And the question as far as Unity is concerned, is cleaning or dredging the solution? And can we have answers without doing the studies?

Q: Prof, what is South Sudan trying to do in Unity State? Cleaning or dredging?

A: I wish to refer you to an MOU that was signed by the late Manawa Peter Gatkuoth (deceased former South Sudan water minister) and the Minister of Water in Egypt. It gave the Egyptians what they did not deserve.

There is a political dimension to this whole affair and the government of South Sudan, although we have very good national experts, and I was there as an international expert, the government is not listening. So, there is a need to review the situation.

There is a need to advance the interest of South Sudan above the interest of any other country or any other entity. It is a very messy fight right now and the fact that there are people who are engineers or graduates does not mean that they can just decide. You cannot decide anything without credible evidence-based feasibility studies.

Q: Does this imply that the agreement that was signed between the late Manawa Peter Gatkuoth and the Egyptian government was not studied?

A: It was not studied and it was kept confidential. For about six or seven months, I did not leave a stone unturned trying to get a copy to study it until finally during the public consultations, the outgoing Undersecretary felt embarrassed when he saw that I was a guest of the president himself and he decided to give me a copy, which I made public.

Every document of the government of South Sudan, unless it is confidential, is in the public domain, and we and others have the right to see it and to criticize it. This is what governance is about, this is what democracy is about.

That agreement was a sell-out, and when I shared it with an expert from the United Nations, he said: “Professor Tag, this is not a sell-out, it was high treason.” The MOU was very ugly. It was a total sell-out to the Egyptians for about $24 million. God knows where the money went. I talked to the outgoing Undersecretary, he didn’t have a clue where the money was or in which bank and what was being done about it. So, we need to be careful who signed it, with what technical advice, with what political advice, and with what authority.

Q: Professor Tag, if this MOU was a sellout to the Egyptian government, could it be that it was done by the Ministry of Water Resources without the rest of the government being aware?

A: I am not sure if the Government of South Sudan was aware of it before signature. They may or may not have been aware of it after the signature but the agreement somehow went underground when I started looking for it. Someone knew that I could not be cheated if I read any agreement about water anywhere in the world, I will know what you are doing.

The document completely went underground until I managed to dig it out and now it is in the public domain. I am not sure how the document circulated or did not circulate. I am not sure if it had the blessing of the Council of Ministers, and the president or if it was presented to parliament. You do not sign an agreement with a foreign country dealing with one of the major resources of the country without having the blessing and the approval and the scrutiny of the legislature of the country.

Q: What are the effects of dredging or clearing rivers on the ecosystem?

A: One of the other projects that are related to water in South Sudan is the Jonglei Canal which is typical dredging because you are tampering with the natural path of the water in Bahr el Jebel and changing it into a canal. That is massive, violent, widespread dredging of the water. That project started during the colonial period in 1904. Today, it remains a colonial project.

Anybody who is talking about the Jonglei Canal is betraying South Sudan. Take the Sudd, it is the largest wetland in all of Africa. It is the second largest wetland in the world after the Amazon. The evaporation from the Sudd is what gives us rainwater when the north easterly winds come and take the moist air and it falls as rain in the western part of Central Equatoria and all of Western Equatoria and northern Uganda. That is one effect. The second thing is that the Sudd is the Ramsar designate. Ramsar is a town in Iran and this is similar to the UNESCO World Heritage and we have applied that the Sudd becomes a UNESCO World Heritage.

(Ed: A Ramsar site is a wetland site designated to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, also known as “The Convention on Wetlands”, an international environmental treaty signed on 2 February 1971 in Ramsar, Iran, under the auspices of UNESCO.)

These are important international law and international organizations designations that in the future will be useful for us in the protection of our ecosystem and even tourists would want to come and see them.

The third thing is that from the Sudd water sinks underground and it will reach underground water so that when you are drilling wells in the villages, you can have water.

However, if we want to do anything in a balanced ecosystem like that, we need to do the studies first and make sure that we do not end up with unintended negative impacts. That is always an important issue. You might want to do well but inadvertently, you go and do something adverse and not pleasant. The only way you can avoid that is to do credible evidence-based feasibility studies. So, it is an issue for us that we do not do anything in our water systems.

We have got Bahr el Ghazal basin and we have got Sobat basin. Bahr el Ghazal basin is 100 percent South Sudan. It originates in our land, it runs in our land and it pours into Lake No which is within our land. Part of the Sobat basin originates in South Sudan and part of it originates from Ethiopia through the Piver Paro. Both Sobat and Bahr el Ghazal run within South Sudan and we can claim a lot of ownership of them, and we can have a lot of benefits from them.

Q: Is this dredging or clearing of the rivers going to have any positive or negative impact on the region? Especially in Sudan, Egypt, or Ethiopia?

A: Yes, it will have a negative impact if the water is drained and the Sudd is drained. The Egyptians since 1904 wanted to drain 4.5. Billion cubic meters additional from the Sudd will be detrimental. That will impact the degree of rainfall in northern Uganda, it will impact the rainfall on all the Equatoria region except for Eastern Equatoria, which is a little bit far from the direction of the wind.

And then we have got people who are living on the movement of the Sudd. The Sudd comes down to about 37,000 square kilometers at the times when there is no flood, and it goes up to about 70,000 square kilometers during the flood season. The wildlife has adjusted itself to this movement of the Sudd and the pastoralists have adjusted their movement away from water and path to that cycle. So, why on earth are we disturbing that? To whose benefit are we disturbing that? If I were a South Sudanese, I would want to see that the interests of my citizens come first and foremost. So, we need to be careful also with our relationship with our neighbors. Are we politically aligned with our brothers and sisters in the Lakes region? Or are we politically aligned with the countries up north? A big question for our politicians to answer.